|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

-Saxon church had only a very short and very tall chancel and nothing else. So the base of the tower would have been the nave. That coincidence of the two Bartons grows when you realise that Barton-upon-Humber was also one of that exclusive list of churches that was turriform. The chancel was replaced by the Normans who built a much longer aisle-less church east of the tower in the first part of the twelfth century with nave and new chancel. The fine south doorway with zigzag and beakhead decoration survives but like many of its contemporaries it has been reset into the outer wall of a later south aisle. It was probably later than the nave itself. Inside the church there are fine sections of Norman blind arcading that flank the chancel beneath Norman string courses. Then in fairly normal fashion, the chancel was extended eastwards slightly and a typical Early English triple lancet east window was installed and still survives. A priests door was also added on the south side within one of the Norman blind arches. Then a little later in the thirteenth century aisles were added: the south first in 1230-50, then the north twenty years later. Not unusually, however, the growth of the building was proving too much for the foundations and a century later it was all bending outwards and in danger of collapse. The north aisle was rebuilt with decorated style arcade. Windows were replaced in various places to admit more light, especially on the south aisle where ogee-arched Perpendicular style windows were installed. They are attractive. The same cannot be said for the rectangular chancel windows that were put in twenty years later. Bits and bobs were altered in the usual way but the last structural piece of the jigsaw came in the fifteenth century when - inevitably in this region - a clerestory was added, again with rather industrial-looking rectangular windows. More excitingly, a chancel screen was also added in the fifteenth century. It is said that it was moved here from elsewhere to avoid the depredations of the Commonwealth and never returned. It was left outside for a long time and the weathering is still apparent. It has been heavily restored, of course, but is still the original and still striking. All of this said, and its parishioners will hate me for saying it, but everything about this church is just a supporting cast for the star of the show - the Anglo-Saxon tower. |

|

|||

|

And here it is, seen from the south side. It is quite remarkable in every way. The curious “half-timbered” look is created by the use of stone “pilaster strips” or “stripwork” by Anglo-Saxon masons who were more skilled in the use of timber than of stone. The elaborate lay-out of the strips invites us to believe that that they are decorative and Simon Jenkins repeats that suggestion. In fact, they intrude into the tower by a distance of ten to forty centimetres. The wall structures are made of rubble that has been bonded by mortar, thus the intruding pilasters help to reinforce the structure as well as, without a doubt, serving a deliberate secondary purpose of decoration. This is amply proven by the remarkable and utterly charming embellishments of saltire crosses and arcade shapes. Other things to note - we will be looking at several other aspects later - is the remarkably clear demonstration of “long-and-short work” at the corners of the tower - that is stone laid alternately vertically and horizontally and perhaps the most irrefutable feature of pre-Norman work. |

|||

|

|

All four sides of the topmost stage has this arrangement of five shafted openings. Making the balusters of equal diameter evidently defeated the masons. Each head is inscribed carved from a singe carved stone embellished with crude semicircular striations. The stonework above the bell openings is fifteenth century. No tower in England, it seems, could escape embattlement! Note the rough geometry of the stripwork top left. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: These double openings are also separated by turned balusters. Note that the stone window openings themselves are cross-shaped and that there are carved crosses over both of the heads that, again, are carved from single blocks of stone. The stone itself - each head a monolithic block - is from the famous quarry at Barnack in modern Cambridgeshire that was used at three cathedrals. You can see the remains of the open-cast quarries today where the ground (a favourite dog-walking spot so wear your wellies if you pay a visit) is known locally as the “hills and hollows”. To the left of the openings is a carved consecration cross. Right: Above the double openings are doorways These existed on every side except the north, although that on the west side has been partially blocked. The question as to what they were for tends to be studiously avoided by the gazetteers but the only plausible idea I have heard was expressed to me by a local supporter of the church on my first visit: that the doors were there so that priests could reveal relics to the congregation below on “special” days. Another possibility is an external wooden walkway around the tower The relatively unbroken nature of the pilaster strip immediately below the doorways tends to discount that idea, however. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The north side presents a less appealing picture, only partly due to failing light! There is no doorway and there are no blind arcade pilasters. although the saltire cross-like decoration was used. This is a good aspect from which to observe the quintessentially Anglo-Saxon triangular headed opening that is repeated on all four sides. Is this less-loved look another manifestation of the widespread belief that the north side was “The Devil’s Side” as discussed frequently on these pages? Is that why there is no doorway? Would the congregation have balked at standing to be addressed on that side? Centre: The west side, partly obscured by a pesky tree! The first thing to note is the Anglo-Saxon west door that would have been the only entrance to the original church. Like so much of this tower, its design is quintessential Anglo-Saxon with its hefty impost blocks and a detached pilaster moulding encompassing the whole doorway. The later west window is a little unfortunate as it has entailed the loss of the double window opening that mirrored that on the south side. You can still see the arches and the crosses that decorate them. Those gurus of Anglo-Saxon architecture Taylor & Taylor believed that the west window itself is no later than early Norman but that the head of the window was replaced later. The masonry certainly suggests both of these things. The arched doorway has also been partly filled in and a slightly bizarre baluster inserted into the surviving arch. Right: The south west corner. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

The tower from the south east. Both the triangular opening and the round headed doorway are on different levels than on the other three faces. The existence of a doorway here seems an oddity until you realise that the pitch of the roof today is much shallower than the original. The roofline would have formed an acute angle with the doorway - you can see the interruption in the stripwork - giving access to the interior of the church, not the exterior. The same geometrics account for the greater height of the triangular-headed opening that would still have looked onto the outside. Why would there be a doorway to the inside of the church from the tower? Well, this is a fairly common feature of Anglo-Saxon west walls. There might well have been a ladder inside the church giving access to the ringing chamber. At some other Anglo-Saxon churches (such as Deerhurst in Gloucestershire and nearby Brixworth) those doorways might have given on to a wooden inner gallery around the west end of the church, possibly for liturgical purposes but at Earls Barton that is impossible because of the pitch of the roof. Indeed, it is instructive to compare the extreme differences in the plan and the scale of the turriform church here and the basilican plan used at the much more important and much earlier minster church at Brixworth. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the triangular-headed openings. The Church Guide suggests - without a great deal of conviction - that they may have simply been lookout windows. That would explain the fact that even the unloved north side has one. You can see that the roof of the opening is comprised of more than one block. The picture gives a remarkably clear demonstration of how Anglo-Saxon stripwork was approached by the masons. The stones are shaped, to our eyes, only very approximately and it seems that the overall effect was what mattered, not stylish execution. It cannot be said too often that building in stone was not a long-established British skillset. The Romans, of course, had it but seemingly took it with them when they departed these shores in the fifth century. The Anglo-Saxons built churches and homes mainly of wood, as they had done in their homeland. The pre-Norman churches we see now are a very small minority of survivors of a very small minority of stone churches, often minster churches serving the spiritual needs of quite large areas, although there is little evidence that Earls Barton was one such. Stonemasons must have been in a small minority and it is clear that they often adapted carpentry techniques to this very different material. Right: The impost blocks of the west doorway are carved with this simple and much-faded three arch design . |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Norman south door. It is very finely executed and one might, without intending any insult, say that it is bog-standard Norman! There is none of the elaborate historiated imagery that can be found elsewhere, especially in the Yorkshire area. Two courses of chevron decoration encompass one of beakhead moulding. The capitals are plain and there is no tympanum. If the outer course of chevron looks a but higgledy-piggledy that is because the doorway was moved from the Norman nave south wall to the south wall of the thirteenth century south aisle. The inner course seems to have been less of a challenge for the thirteenth century masons. It dates from about 1080. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

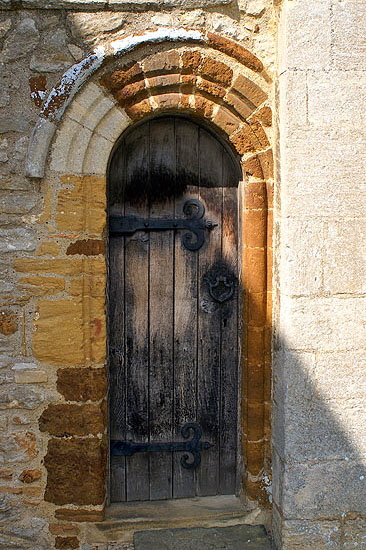

Left: the Anglo-Saxon west doorway. Centre: The priest’s door on the south side is part of the Norman chancel. It has been partly obscured by later masonry. Right: After the ancient certainties of the tower, the tower arch within is, pardonez mon francais, a buggers muddle. The masonry atop the euphemistically-named “arch” is clearly Norman and equally clearly was not in this location originally. It rests partly, at least, on Anglo-Saxon columns. Not to put too fine a point on it, it is remarkably ugly; the result of at least three lots of bodging. It is in sad contrast to the many attractions of this church. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end, and I have said all I am going to say about that tower arch! Centre: Looking through the chancel screen to the chancel beyond. It is tall and narrow. To the left can be seen Norman blind arcading (its counterpart on the right being hidden in this picture) and they mark the extent of the Norman chancel. The extension to the west is thirteenth century as evidenced by the original Early English triple lancet window. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking from the south aisles across to the chancel arch we see the pretty wooden rood screen. It is heavily restored, of course, and has been furnished with a replacement rood. Archbishop Cranmer, let me tell you, as well as Edward VI will be amongst many other “reformers” those turning in their graves! Right: This is is a very odd carving indeed and it is oddly-placed in the corner between the tower and the south aisle. I am guessing that it is a survivor of the Norman nave walls before they were submerged beneath the later aisles. Quite what it is, nobody seems to know. There is little doubt that a man is drawing a bow and arrow on the right side. To the left, however, there seems to be a pair of wings. Sagittarius is a staple of the Norman “design book”, especially on corbel tables, but I can’t seen any way this figure has the body of a horse. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The Norman arcading on respectively the north and south sides of the Norman end of the chancel. Note also the Norman string courses above the heads of the arches. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 : Turriform Churches |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are no surviving turriform churches in Britain in their original form and it is not hard to see why. A turriform church was essentially one that was entirely dominated by its tower with the nave in its base and which usually had between one and four very shallow “wings”. Such churches would have been wildly impracticable for all but the smallest congregations so today we see only a few vestiges of them, of which Earls Barton is one of the best examples. The concept is not a well-known one. I first encountered the concept in “Parish Churches - Their Architectural Development in England” (Faber & Faber 1970) by Hugh Braun. I still rate this as the most readable and approachable book on the subject with great additional virtue of brevity (250pp). Braun, I have come to realise, was not one of the magic circle of writers on architecture and had views that were sometimes unpalatable to his peers. He was unapologetically scathing about what he saw as the narrow and classics-saturated artistic curriculum of the great public schools and universities of the time which, he felt, suggested that Romanesque architecture with its roots in Greek architectural forms was the zenith of British ecclesiastical building development; and that everything after it was more or less rubbish until the neo-Classical style emerged in the seventeenth century. Lest you feel this is an overstatement I refer you to the fact that the word “Gothic” means “of the Goths”; those very Goths who until very recently had been called “Barbarians”. Gothic was not meant as a compliment! The Goths were not Barbarians and, ironically only a philistine would regard gothic architecture as barbarous. Braun felt that this unbalanced education caused the Western Roman Empire of the City of Rome itself, and latterly of Ravenna to be lionised by the intellectual elite at the expense of the much longer-lived Eastern Empire - later the Byzantine Empire - based in Constantinople. The churches built in the Eastern Empire in the first millennium were characterised by a central tower-like structure surmounted by a dome and surrounded by a number of small apsidal sub-chambers. The ultimate product of this style is nowadays seen in the great mosques of Islam, such as the Emperor Justinian’s sixth century Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. President Erdogan has just (2020) re-designated the building as a mosque, a role which it has had before of course, but the Hagia Sophia started life as a Christian church. Domes did not appear in English architecture, of course, until Wren’s new St Paul’s Cathedral. In continental Europe some domed cathedrals were built but the self-supporting dome was an enormous challenge to western architects and insular Britain was centuries further back on the learning curve. Even today, although St Pauls is no longer unique in Britain, the dome is not a common part of the architectural palette. It was Braun’s contention that the turriform church was an emulation of Byzantine style but with the tower replacing the problematical central dome. He was in no position to prove this provenance, and it sounds obscure. That it should sound thus is, I think, a function of the relative obscurity of the Byzantine world. We all go to Italy to see the cathedrals and we go to Turkey to see the mosques, forgetting that Islam itself dates only to the seventh century AD and that even then it was seen initially as a heretical form of Christianity. When we learn of the Roman Empire at school we think of, well Rome! We think of Romulus & Remus, Julius Caesar, Augustus, Nero, Spartacus (I am he!) and all that lot. All peace-loving liberal democrats, of course. Our “English” Romans retreated to defend Rome the city, or so we are led to believe, from those wretched “Barbarian Hordes”. Go to see the glories of the Ravenna of the Gothic Emperor Theodoric if you believe that Roman-inspired propaganda! If you don’t “buy” the Byzantine influence then it is very difficult to work out where the idea came from. We know that the Anglo-Saxons didn’t go a bundle on stonework. Why on earth would they think of this form of church which probably had the highest aggravation to floor space ratio of any church design without some motive? Also bear in mind that we are increasingly recognising the Byzantine influence on pre-Norman sculptural art. See in particular my page on Breedon-on-the-Hill for more about this. So where, besides Earls Barton can we see these odd churches? Barton-upon-Humber in North Lincolnshire just south of the Humber Bridge is very reminiscent of Earls Barton. There is widespread acceptance that these churches were indeed turriform, not least by Taylor & Taylor whose three volume work “Anglo-Saxon Architecture” (Cambridge 1965) is awe-inspiring in the thoroughness of it research. They also claim Broughton in Lincolnshire as having been turriform. They do not, however apparently agree with Braun about Breamore (Hampshire) and Barnack (Cambridgeshire) and several other churches claimed by Braun to be turriform although we have to remember that Braun wrote his book five years later. Where we must take note of Braun is when he suggests that many of the timber pre-Norman churches of which, of course, none remain were centred on a timber tower-nave. As he says, the main requirement would simply be for four long stout timbers to frame the tower. This proposition is the only one I have seen so far (although I have missed others, of course) as to what form these pre-Conquest timber churches, to which Church Guides and books refer so airily, may have taken. Many leave you with the impression that these were all thatched huts. Many may indeed have been so, but surely not all. Braun made a comparatively rare distinction between the Angles and the Saxons. Most of us are used to talking airily of the “Anglo-Saxons” - and every history book does - as if they were one and the same people, not to mention omitting the Jutes (who dominated Kent) and the Friesian insurgents altogether. Braun does make the distinction and it is a geographical one. The fact is that the Saxons settled mainly in the south and west of the country; hence Sussex, Wessex, Essex and Middlesex (that is “South Saxons” and so on). Most of the east of the country was settled by the Angles; and Braun believes it was the Angles who were mainly influenced by the Byzantine Europe. Thus, the two Bartons and Houghton are both in the Anglian part of the country. I would add (although Braun did not) the Byzantine art of the churches of Breedon-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire and Fletton in Peterborough. Anglianism can also be identified by the plethora of pre-Conquest churchyard crosses that are found mainly outside the areas settled by the Saxons. With the exception of the two Bartons and of Broughton in Lincolnshire there is so no consensus about other stone churches having been turriform, although it is interesting to note that Taylor & Taylor themselves listed three in Scotland: Dunfermline, Restenneth and St Andrews. The truth is that pre-Norman stone churches have been through so many changes that it is going to be contentious in most places. That the form existed, however, is beyond doubt and Braun is surely right in suggesting that there were likely to have been many such timber tower-nave churches in pre-Norman England. Finally, I cannot help asking myself if Wootton Wawen in Warwickshire was originally a turriform church? It has a remarkable pre-Conquest tower with surviving doorways at each of its cardinal points. Although there is pre-Norman fabric within the nave, this is of a later date than the tower. Did that tower originally function as a nave with four wings? I have never seen it discussed and Braun did not mention it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

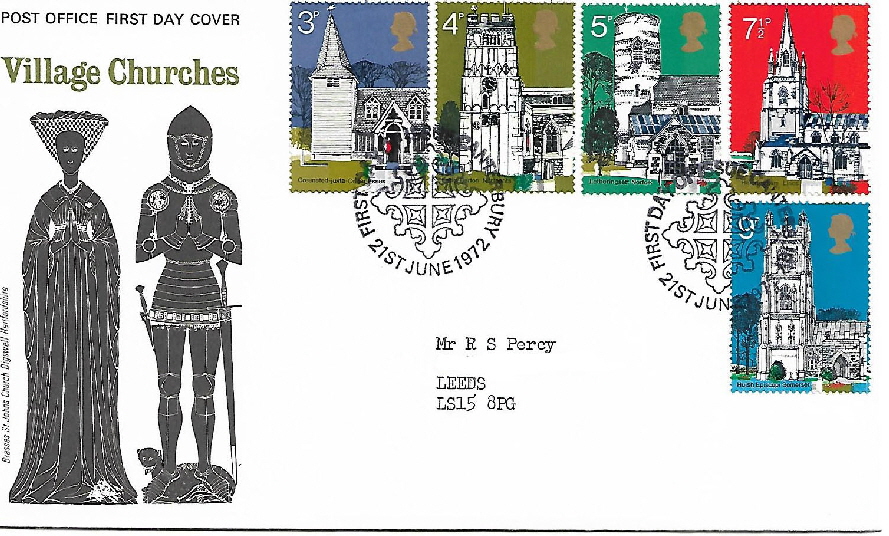

Footnote 2 : British Commemorative Stamp Set |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Like most postal administrations, Britain’s Royal Mail (and before it the Post Office) is addicted to commemorative stamp sets. It isn’t hard to see why. You bung some money at an artist who designs you an attractive set of gummed labels. You then print off gazillions of sheets of the things, putting on them whatever price you like and flog them to the public. The clever thing is, of course, that other than at Christmas the vast majority end up being bought by collectors who thus pay the administration not to send letters and parcels. It’s a wizard wheeze. The First day Cover takes that a step further. You pay an inflated price for a “special envelope”, stick on a set of said labels and then mail it to yourself on the day the set is issued - in this case 21 June 1972 - and it arrives with the stamps neatly cancelled with a “special” handstamp (or nowadays I imagine a machine stamp). The marginal cost of the Post Office carrying it is infinitesimally small and you make a nice additional wodge of cash. There used to be heavy hints about “investment potential” and “collectability” but needless to say the bric a brac shops of Britain are awash with this stuff at knock-down prices. There is only one winner and we all know who that is! “Special stamps” on “special envelopes” with “special handstamps”. How gullible are we? Funnily enough, and I know you will find this hard to believe, the numbers of “special stamps” rise inexorably each year. Similarly amazing is that the justifications for the issues have become increasingly spurious (Star Wars anyone?) and the quality of the art increasingly dubious. Mind you, Diana and I succumbed a few years ago and bought a “Winnie the Pooh” set. Come on, we just love that bear and little Piglet! Just don’t ask me where the stamps are! Anyway, I think this set from 1972 is actually nicely done, promotes the best part of Britain’s heritage and the face value of the stamps pre-dates the much worse rip-offs to come. The reason for including it here is that the 4d stamp - the first class letter rate of the time - is of Earls Barton. The others are : 3d Greensted-juxta-Ongar (Essex); 5d Letheringsett (Norfolk), a Norman round-towered church ; 71/2d Helpringham (Lincolnshire), an admittedly fine church sporting examples of all three Gothic styles (as well as a Norman font) but hardly exceptional; 9d Huish Epicscopi (Somerset), with an exceptional gothic tower in a county renowned for those. They were designed by the renowned Ronald Maddox (1930-2018). Stuart Rose the Post Office Design Advisor noted that “to condense 600 or 700 years of ecclesiastical architecture into five little stamps is no mean feat”. Despite my cynicism about “special stamps” I would agree with that. This is a nice set and Maddox chose a decent set of churches. But, oh lord, no Kilpeck??? Not that I am biased, you understand. But it seems that Maddox needed all of the churches he used to have a west tower to promote a uniform “look” and to fit nicely into the vertical format of the stamps’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||