|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

practice, but why Norman lords were doing this a century after the Conquest if something of a mystery. Was it cultural imperialism? Was it because English monks were perceived to be somehow inferior? Or was there just a surplus in French houses? Either way, it re-emphasises that as far as the Norman families - and their kings - were concerned their lands in England and France were inseparable, an attitude that persisted and caused cross-channel conflict for half a millennium. Nothing remains of the monastic buildings. The original church may have had a central tower and crossing with transepts. It almost certainly had an apse as well. It served as the parish church as well as the priory church and this would have been the main reason for its surviving the Reformation. However, as was so often the case, relegation to parish-only status led to a much diminished building. The clerestory was removed. The glazed upper storey we see today was once the triforium: the intermediate stage between arcade and clerestory. It was The apse - that symbol of monastic mystery and exclusivity - was demolished. If there was a crossing and transepts they too were removed. The north aisle went the same way. In other words, all that was really left was the nave and that in reduced form. The most important survival was the extraordinary Norman west front with a west door that Simon Jenkins rightly describes as “an astonishing composition, dated c1150 and reminiscent of the great chancel arch at Tickencote (Rutland)”. We are going to be talking a great deal about this west front but at this point I will simply say that it is one of the truly great survivals of the English Romanesque, Then in 1866 G.E.Street arrived. Street (1824-81) was responsible for building and “restoring” dozens of churches. One might argue that some of his restorations were tantamount to vandalism. It is easy to forget, however, that many churches at this time were in a structurally parlous state and needed drastic surgery. Moreover, we must acknowledge that he and his fellow architects were children of their time, influenced by such cultural fanatics as Morris and Ruskin, by the Oxford Movement and by the “Gothic Revival” - all of these things intimately entangled. We must acknowledge also that parishes and patrons would have also been thus influenced. It is too easy to blame the architects alone. We must also remember that the primary function of churches then was as places of worship, not as architectural museum pieces Street liked apses, so the large one we see today is his. Yes, it is outsize and yes it is arguably a bit silly from a functional point of view, but a print 1812 shows the church as an aesthetically unappealing rectangle of masonry. One might argue that the apse was an ingenious way of softening the whole look of the church. The north aisle was replaced in 1820 by Joseph Bennett. To me it is undersized and unappealing but it is unequivocally an improvement on the slab sided north wall that had been left by the Reformation. Pevsner termed it “an odd conceit”! And so to that west wall. Jenkins says of Street: “He inserted shafts into the central doorway, added new windows and arcading wherever fancy took him and retooled individual carvings” Elsewhere he wrote “Even Street could not detract from Tutbury’s glory”. I have to say that nineteenth century prints reveal the disaster area that probably confronted Street. In fact, although the west front makes an enormous visual impact the Norman elements comprise no more than that wonderful west doorway and a west window flanked by two short sections of blind arcading. I am struggling to see any “inserted arcades” or “new windows”(as opposed to restored ones. The main Street-ism here is heavy re-carving of the five columns either side of the west door and around the west window. It is arguably heavy-handed but much (although not all) of it is in the Norman tradition and in my view detracts little from the ancient beauty. I must say that, much as I love Tickencote Church, its restoration was much less successful. I think I’ve talked more than enough. Let’s take a look at the church! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

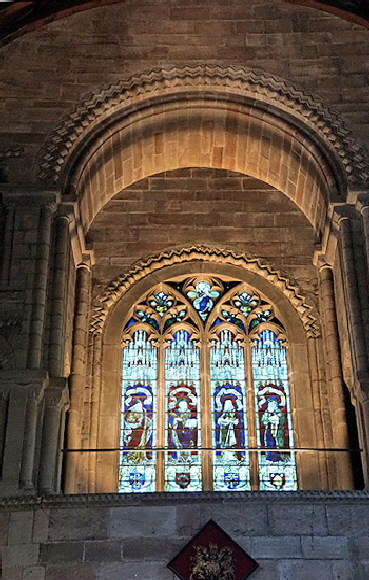

Looking towards the east and G.E.Street’s apse. The clerestory was the original triforium. Originally it would have been unglazed and above it would have been the original clerestory. That arrangement was very much a monastic one and surely was not part of the original church of 1080. That is true, in fact, of much that we see here. Pevsner dates the columns to the early twelfth century and that would be reasonably consistent with the foundation of the priory. Note that the two easternmost bays have circular columns whereas those further west are of a compound design. They are, however, certainly contemporaneous. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The view to the west. You can see that the west window space is flanked by original blind arcading. The west window itself is a curiosity. Antique prints show it with intersecting tracery of an early Decorated style design. It is now filled with nondescript faux-Gothic tracery apparently installed about 1890. The inside of the window space seems to be original Norman. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

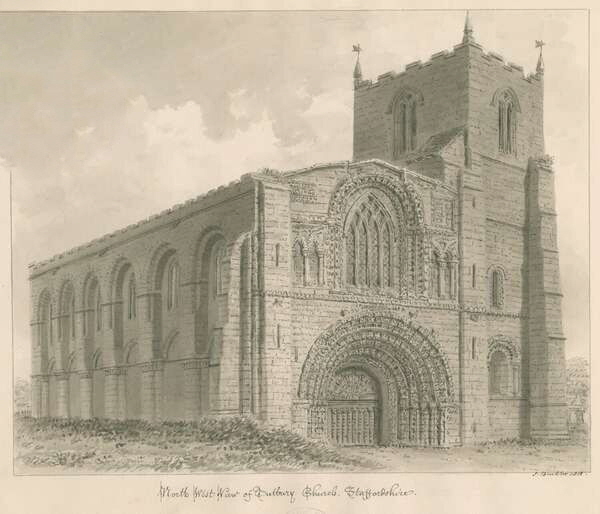

The west front. Unfortunately, the lovely ladies who were minding the shop park their cars in front of it! The south west tower is Norman in its lower stage that would have been part of the south aisle. The upper stages are much later, perhaps coincident with the demolition of the putative Norman crossing or perhaps this was the only tower. If the west front is this church’s glory then the doorway is the glory of the west end. We will be looking closely at that. Street literally raised the roof. Antique prints show a shallow roof that left little headroom above the west window. It looked aesthetically dreadful. The gable with its three oculi restored a sense of proportion to the church - and you can see the pleasing effect it had on the interior in the picture above. The west end of Bennett's north aisle adds nothing to the beauty of this composition, I am afraid. Not there are stair turrets to both north and south. The one to the south gives access to the what was originally the gallery (or triforium) within. The large window at the bottom of the tower is intriguing. The eighteenth century print shows this as a doorway to the tower with a flight of steps leading up to it. This proves the Norman provenance of the lower stages. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The west door. To avoid distraction I have photoshopped out the blue car you see in the picture above! The doors are not as tall as this! There are six courses of decoration here as well as the outer hood mould. Street seems to have responsible for that uninterrupted inner course of zigzag moulding as it is not visible on the old prints. Very obviously. Street recut all of the columns and it is not clear to what extent he copied what he found or whether some of it is “in the style of”. The capitals, however, were untouched as was, apparently, the courses of archway decoration. The old prints vaguely show a tympanum which looked to have a geometric design. You will notice that the second courses is in lighter stone than the others. That is because it is of alabaster. Jenkins says it is the first known use of alabaster in England . This is a grand claim and I am afraid it is not his own. Pevsner said it first and Jenkins repeats his mistake of saying it was used in the outer arch. Oops. The Church Guide says it is the only use of alabaster on an exterior arch in the country never mind the earliest and I am sure that is true. It was restored recently. Alabaster is best-known for its use on late mediaeval church monuments but I know of two early (but not Norman) alabaster fonts in Cumbria - see Crosscanonby. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The decorative orders of the west doorway. They have suffered somewhat but I think we can be grateful that Street left them alone! The alabaster course is second from the bottom with miniature beakhead carvings. The fact that alabaster was used on this second reinforces my belief that the zigzag course below it was Street’s own invention. The alabaster course was surely the original inner most one. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Back inside again. Left: The west wall with its attractive blind arcading. Centre: The west window. Look at the inner arch and compare with the outer one. The former is finely executed with regular voussoirs decorated with zigzag. The outer arch is a mess and looks to be cobbled together, presumably when the tracery was installed in 1890. I suppose this bodge job was invisible before the days of telephoto lenses. Right: The west end of the south aisle. This is actually the base of the tower. The old prints shows the west window as being a doorway with a a flight of external steps up to it. The proportions of the arch - it looks too short for its breadth - support this. So how did this work on the inside? The small doorway to the right is presumably to the tower. How this doorways were configured together is a mystery to me! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are some interesting lengths of Norman string course around the west end of the church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south door. It has four orders of decoration, all stylised apart from one or two badly weathered beasties on the outermost course. The lintel showing a boar hunt is the most interesting feature although it too is badly weathered. The Church Guide declares the whole thing to be a patchwork as it has been used as a window until 1913. This seems very odd as the arches, lintel and capitals clearly are from a doorway! There is probably an old picture around but I have not tracked it down. The Church Guide makes the rather odd statement that this door was used as a window until 1913. I have seen an antique print of 1812 that would seem to refute this. Centre and Right: Street’s columns on respectively the north and south sides of the west doorway. The two beakhead-style courses nearest the door are quite authentic, albeit jarringly “new”. The outer ones, however, show disappointing lack of imagination and are careless of the Norman sculptural traditions. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The badly weathered capitals of the south doorway. Only one of them (centre, right hand picture) is vaguely discernible: three figures with arms raised. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another view of the capitals of the east side of the south doorway, part of the abacus has clearly been recut, although seemingly copying an existing design. Right: The lintel with the boar. There were hounds too, but they have been badly weathered. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Above Two Pictures: The respectively south and north sets of capitals of the west door. It is very obvious that Street used some of the beakhead designs for his re-carved columns. Nobody seems to have attempted to say what these weathered scenes are meant to represent. We might have struggled to get inside the early mediaeval mind even if they were fresh! So I am going to limit myself to saying that the second capital from the right on the north side (lower picture) shows a Sagittarius figure firing his bow at some kind of bird which has also has a beakhead grasping it! |

|

|

|

|

Left: The west window and gable. I have already discussed the window at some length. It is surrounded by decorative courses. If you look at the decorative courses around the top of the window you can see confirmation that there was some reconfiguration of this arch, confirmed by the messy state of the inside of the arch (see above). It is difficult to know whether the zigzag course is original or whether Street was repeating what he did on the west door. But it is very clear that the replacement of the tracery early in the twentieth century led to the insertion of the incongruous, if inoffensive, inner course of fleuron decoration. The window is still - just - something worthy of study as a basically Romanesque window but it could also stand as a monument to misguided “restoration”. Oddly the generally unimpeachable “Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland” lists the three round windows (“oculi”) in the gable as if they were original Norman. This is clearly not the case as the roofline was much lower until the G.E.Steet restoration. Centre and Right: The courses of decoration to left and right of the west window. The outer courses of beakhead mouldings and the decorative roundels outside them look to be original. There are some signs of minor restoration work, however. |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

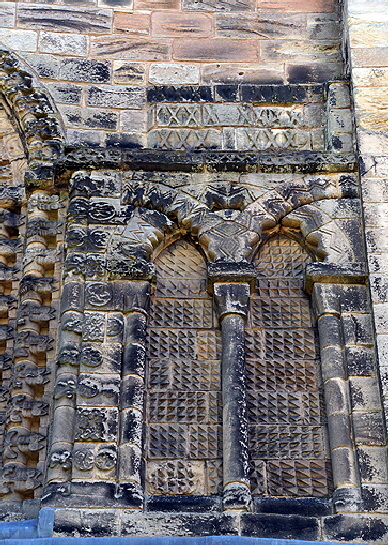

Left: The south west tower. Centre: Blind arcading to the south of the west window. There is similar on the north side. Note the roundel patterns to the left adjoining the window. Right: Norman lancet window in the Norman lower section of the tower. |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: One of the original Norman north windows. It has been much restored, Centre: The door looks ancient with its serpent headed hinges. Right: The tower complete with Narnia lamppost! Strangely, the window visible at the base of the tower is shown in the prints to have a mean little porch partially blocking it. There is no sign of this - see my comments below, |

|

|

|

Left: Detail of the blind arcading to the right of the west window, Right: The clerestory from the inside. This was originally the gallery or (triforium).Gothic windows were inserted during the post-Reformation re-purposing . Interestingly, though, there is no sign that this triforium had a passageway as was the case in many such features. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

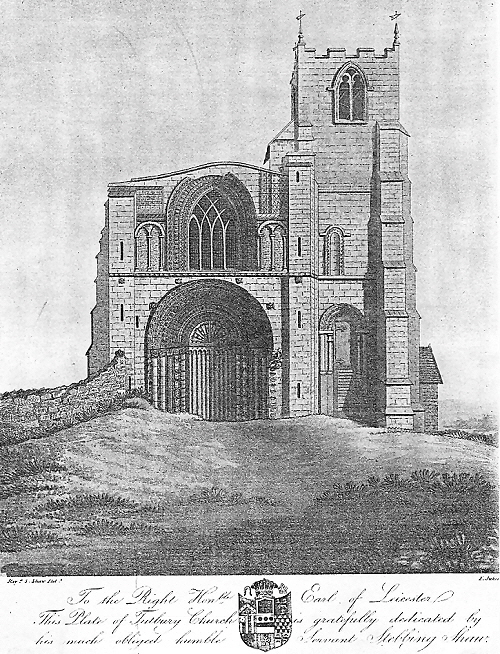

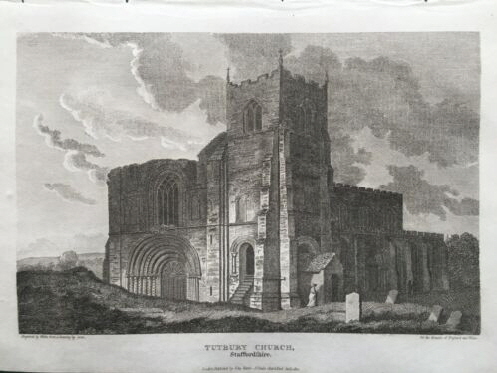

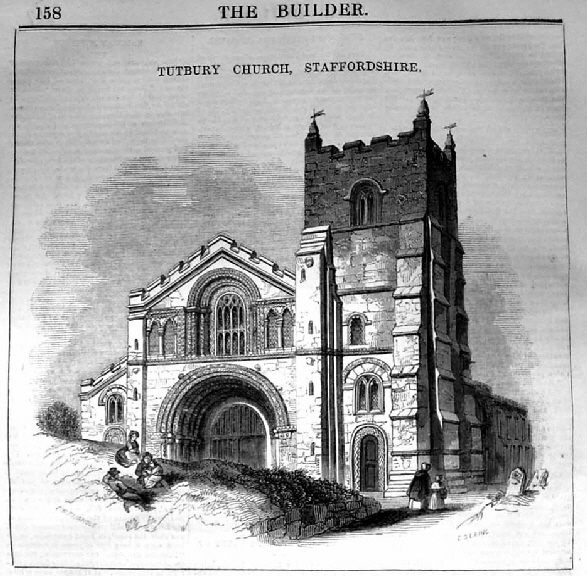

Left: Another picture of 1812-14 by William Carter. Note the odd little porch shown on the south side of the tower, partly obscuring the existing window. If you are not already confused (I certainly am!) that stairway to the west window of the south aisle has re-appeared! Right: This is a particularly interesting print. It is from a publication called “The Builder” and is undated. Moreover, it has quite a long article associated with it. In trying to unravel what was going on at Tutbury, this article is invaluable. Because a north aisle is visible, we know this article post-dates its 1820 building by Bennett and must represent the church which G.E.Street worked on. In fact, the article might even have been prompted by Bennett’s program of work. Comparing it with the earlier prints, it is clear that Bennett did more than build the aisle. He also battlemented the west end of the nave, giving it a much more “finished” look. Notice in particular that the stairway to the south west door has gone. The text of the article confirms that it had been there, unlikely as it seemed.. Bennett seems have changed the whole section. The doorway was lowered to ground level (and presumably too the floor into which it gave access) and above it he put a round headed window space with characterless gothic window tracery. It is a mirror, it seems, of the window he put into the north aisle visible on the left and which is still there .The Norman window above it looks squatter but I suspect that this was an artistic lapse. Similarly, it is hard to know whether the west window tracery is accurately reproduced here. That porch to the right has gone, however. This shows that the church worked on by G.E.Street in the eighteen sixties was rather different from the one shown in the earliest prints, including the 1801 print that is also reproduced on the back page of the Church Guide. Bennett has already “tidied up” the church. He changed that problematic west end of the tower, removing the doorway altogether and changed Bennett’s window, removing the gothic tracery and resetting the surround. He put in the new roofline higher than Bennett’s own, and installed the three “oculi” to break up the new gable end. |

|

|