|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

from 1713The very rustic-looking two-bay north arcade and its associated aisle date from c12. The column separating the two bays was replaced in c18. The effigy of T.E.Lawrence (that’s “Lawrence of Arabia” to the uninitiated) occupies much of the aisle. It was placed here in 1939 but Lawrence is actually interred in the churchyard of Moreton Church nine miles away. Lawrence died in a motorcycle accident when living at Cloud’s Hill and was a frequent visitor to the town. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view towards the chancel arch. Note that this view is somewhat distorted by my use of an ultra wide angle lens. Right: The view from behind the altar table looking towards the west shows the squints to left and right of the chancel arch. The southern one - to the left of this picture - is an oddity. Squints were to facilitate the congregation’s being able to see the “mysteries” being carried out within the chancel and are normally associated with aisles where the view may have been impeded. But Wareham has no south aisle and, if anything, an unusually visible chancel area. The Church Guide rightly points out that this squint is set into what is a blocked Norman doorway but that doesn’t really answer the question as to why it is there at all. Nor is there any obvious reason why a door should have been there in the first place! The Church Guide talks of its having been there “probably to enable the priest to enter a pulpit”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A closer view of the chancel arch. The little arc-shaped kneelers either side of it draw the viewer’s eye to the arch and are a pleasing addition to this intimate little church. Centre: The north aisle squint. Right: The chancel itself is narrow, shallow and very tall. It is worth comparing with the c7 church at Escomb in Durham. There the proportions are even more exaggerated but it shows that the Anglo-Saxon preference for churches were, to our eyes, disproportionately high had not changed much over the course of 400 years. In all three of these pictures the plethora of paint fragments is very striking. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north aisle with Lawrence monument filling up half of its space! It’s an odd composition, not to say a bit of a mess. The eastern bay is narrower than the western one. The central supporting column is an c18 replacement in different stone from the rest. There are two half pillars supporting the arcade at the eastern end. Add in the ancient “brick” outlines over the arches and it all looks to me rather like the scenery for a play! Right: This is the best part of the wall painting. This is from the c12 and depicts St Martin of Tours, to whom the church is dedicated, as a Roman officer on a horse. In the lower part he is giving his cloak to a beggar. In a vision he had later he saw Christ wearing part of the same cloak. The painting continues into the splay of the Norman window to the right. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Close up of the lower panel of the St Martin of Tours painting. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end. Note the massive timber beams across the aisle roof. Right: The half-capital at the western end of the aisle arcade. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Lawrence’s effigy by Eric Kennington. In many ways, it is also a monument to clerical intransigence and to the ambivalent attitude of the British establishment towards this tortured and complex young man. Lawrence was fascinated by the Arab culture and adopted it enthusiastically during his campaigns against the Turks in World War I. At that time, however, I don’t think it is unfair to say that little respect was shown to middle eastern culture in general and many saw this side of Lawrence as being somewhat distasteful. The memorial was, it seems, as controversial as the man, and it was rejected for place in Westminster Abbey, St Pauls Cathedral and Salisbury Cathedral. The Dean of Salisbury felt that Lawrence should be portrayed in RAF uniform standing upright: a bizarre idea considering Lawrence’s history (see footnote below). The vicar of Moreton Church, where Lawrence is buried, also turned it down on the basis it would spoil the look of his church! That’s the way to treat a national hero, eh? His feet rest against a block of Hittite sculpture representing two fighting bulls, a reference to his own military struggles. In his left hand he clutches a camel driver’s whip. In his right hand (Centre) he clutches the dagger presented to him by King Faisal. Right: The painted arms of Queen Anne above the chancel arch. These only partly cover the previous arms of one of the Charles’s. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

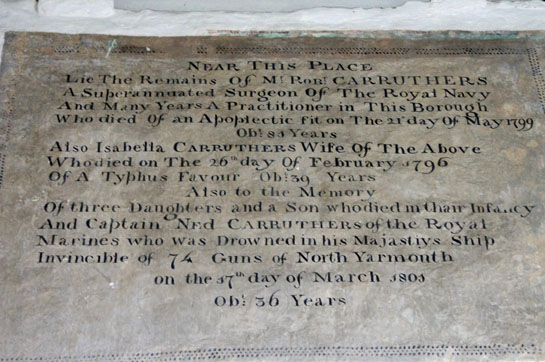

Left: Memorials - often to wealthy nonentities - disfigure many a church, in my view. Some of them, however, present a human face to the most interesting facets of English history. This one, to the Carruthers family, is one such. We have here two generations of naval surgeons, one of whom was drowned on HMS Invincible - a 74 gun 3rd Rate ship-of-the-line - in 1804 at the time of the war against Napoleonic France. This was the second RN vessel to bear the name and she took part in the Battle of the Glorious 1st of June in 1994. What the memorial doesn’t tell you is that Carruthers was one of four hundred sailors lost when the ship was wrecked. Note too the causes of death: “apoplectic fit” for Carruthers Snr; “typhus fever” for his unfortunate wife. Note too, the disparity in the ages of the happy couple - she was forty one years the younger. One can only hope that financially this was a “good match” for the hapless Isabella! Right: The east end with its c15 window. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The original width of the church in the north side is easily identifiable Centre: The Norman lancet window on the north side of the chancel. Right: Blocked lintelled north door. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - The Post World War I Career of T.E.Lawrence |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The British military (like most of its European counterparts) was horribly slow to learn the lessons of conflicts elsewhere. The American Civil War taught us nothing about the carnage caused by charging entrenched defenders armed with modern weapons (and they didn’t even have automatic rifles!). Britain was introduced to possibilities of mobile irregular forces by the Boers in its conflicts there. The very word “Commando” is a Boer one. The British Military handbook changed little. While Generals French and Haig were still hurling hordes of tommies to certain death in France and Belgium, therefore, Lawrence’s methods against Turkey’s Middle-Eastern Empire must have seemed unorthodox indeed. Most of us get our knowledge of his wartime career through David Lean’s film “Lawrence of Arabia”. The final scenes of his memorial service at St Paul’s Cathedral hint at the Britain’s ambivalence towards its first exponent of modern guerilla warfare but do not cover his extraordinary post-war career. Lawrence left the war a full Colonel. In about 1919 he wrote his book “The Seven Pillars of Wisdom” about his exploits. It was published in 1926. By 1921 he had been part of King Faisal’s delegation to the Paris Peace Conference and acted as Middle Eastern advisor to Winston Churchill at the Colonial Office. Then his career becomes distinctly strange! In 1922 he joined The Royal Air Force as an Aircraftman (the very lowest rank) as John Hume Ross. He was interviewed by one Flying Officer W.E.Johns (later author of the “Biggles” books) who guessed that his recruit was using an assumed name. Johns was ordered to accept Lawrence under his assumed name. A/C Ross proceeded to write a book called “The Mint” (I own a copy) about his life in the RAF. It is sub-titled “A day-book of the RAF depot between August and December 1922 with later notes”. The “depot” was actually at Uxbridge. Lawrence insisted it should not published until 1950 because of “the horror the fellows with me in the force at my giving them away in their ‘off’ moments with both hands”. It was not, in fact, published until 1955 and it is liberally (and infuriatingly) interspersed with blanks where profanities have been removed. The earliest unexpurgated versions are worth a great deal more. The introduction by his brother A.W.Lawrence (who also commissioned the memorial at Wareham) gives an insight into T.E.’s thinking. I pick out one passage: “The Air Force is not a man-crushing humiliating slavery all its days. There is sun & decent treatment, and a very real measure of happiness to those who do not look forward or back...” It seems that Colonel Lawrence was, therefore, enduring “man-crushing humiliating slavery” some of the time and all at his own behest! You might wonder how such a man could be one of those who didn’t “look back”. Lawrence’s fame grew and his identity was “outed” in January 1923 and was forced to leave the RAF. He promptly enlisted in the Tanks Corps under the name “Shaw”. In 1926 he was allowed to rejoin the RAF, again as Shaw. He remained a serviceman until about 1934 when he was discharged. Part of that period was spent in India whence the RAF sent him when he received a fresh burst of publicity. It was only two months after his discharge that he was killed in a motor cycle accident near Cloud’s Hill. E.M.Forster and Winston and Clementine Churchill were amongst those at his funeral in Moreton. I make no claims into any great insights into Lawrence’s life but by any measure he seems to have been a strange man and certainly not one likely to find favour with establishment or “society”. His love of the Arab culture would have raised eyebrows. The “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” is thought to have embellished his exploits considerably. He never married and there has been a lot of speculation about his own account of being raped by a Turkish officer and what can be inferred about his sexuality. His story is almost literally incredible. To see his monument with in this little church at Wareham, clad in Arab dress and clutching Arab artefacts is to reflect that Lawrence was a real person totally out of kilter with the England he lived in. To coin a phrase: “You couldn’t make it up”.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||