|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

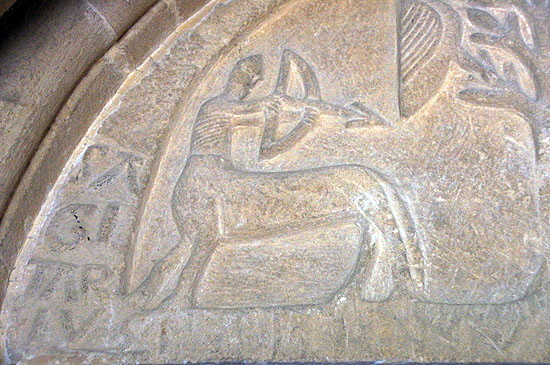

The chancel has Norman corbel tables to north and south. They are big and bold. All but one or two are of geometric design: this is no Elkstone. It is the north doorway, however, that is of most interest. The doorway itself lacks the flamboyant courses of decoration that characterise later Norman work. The door is, however, flanked on either side by free standing shafts with nicely carved designs topped by capitals with simple scroll decoration. The tympanum, however, is what takes the eye. It is naively carved. At the top three birds peck merrily at a tree - possibly a Tree of Life. It is flanked by figures of Sagittarius and Leo. Lest we be confused and think they might be a centaur and just any old lion, the masons obligingly carved their names into the stone. You might well be wondering why mediaeval masons were bothering with astrological imagery, but we see it again and again in Romanesque architecture in Europe and our ancestors were clearly still influenced by Greek mythology and philosophy. Two examples of Sagittarius on this website are Beckford (Worcestershire) and Elkstone (Gloucestershire). There is a lively debate to be had about the symbolism here - see below. The chancel arch is original Norman but has been rebuilt. It is not flamboyant but is of quite impressive dimensions and has a respectable three orders of decoration (although, sadly, no beakheads) and finely-carved scroll capitals. Oddly the two northern shafts are carved with decorative designs whereas those on the south are plain. The north transept followed in about 1190 in the Transitional style with a ribbed vault. The south transept is of about 1300. This has a somewhat unusual window configuration with four lancet-like windows each on the east and west sides. They each have modest cusps so that they look like a transitional melange of Early English and Decorated styles. The heavyweight north porch is a little later and has a quadripartite vault. Thus, the tympanum has been protected from eight hundred years of weathering! The tower, unusually placed on the north side, is thirteenth century. The south and west walls of the church are considerably changed. We can see the remains of the south door and its shafts and structure are similar to the north door. It surely had a tympanum originally and we can only curse whoever it was who decided to obliterate it with a gothic window. Not the least of the peculiarities of this church is the development of its north side. The two-storey porch shows that the north entrance has been the main one since at least 1325. The north tower is thirteenth century. Yet in most English parish churches you will see that the north door is either disused or - more commonly - completely blocked. North sides are generally unloved and for good reason: for centuries this was regarded as the “Devil’s Side”. North doors were used to allow the escape of the evils spirits from baptised infants, not for ingress or egress. Parishioners would not use them. Even today vestries and boiler houses generally disfigure north sides rather than south sides and I have been to many a church where the north side is overgrown with brambles or littered with ankle- threatening broken gravestones! Why did Stoke sub Hamdon develop its north side? In my view it must have been a structural issue associated with the stability of the site or problems with foundations. The biggest cause of collapse in English churches was the addition of hefty extensions to churches that already had poor foundations. More on this later. That’s enough of my wittering on. Let’s look at the rest of the church through the photographs. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north. Note the crowded look caused by the hefty tower and porch. Only the corbel table on the chancel warns you that this is a Norman church. Right: The chancel. The corbels are unusually large and are topped by a Norman string course. It is clear that the roofline has been raised slightly at some point. Some corbels have been lost to intruding buttresses. These are not Norman and I would guess that they were put here to help cope with the addition of the tower. The windows are a messy configuration and it is hard to see how they relate to the original - presumably more ordered - Norman windows. Note the unusual westernmost window that has a transom a third of the way up. This formed a “low side window” that would have been shuttered. Very unusually the configuration is repeated on the south side. Traditionally these are known as “leper’s squints” based on the nonsensical idea that lepers were part of the community and free to observe church proceedings - including those hidden from healthy parishioners by the screen - from the outside. Fortunately, Lesley Strutt the churchwarden and author of the Church Guide who showed me round, also thinks it’s nonsense so we didn’t have to have an embarrassing conversation! She suggests that the low side windows were to allow a bell to be rung to indicate the consecration of the wine and bread to those outside. It’s as good a theory as any I’ve heard. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south east. The chancel windows are uncusped on this side and more Early English in appearance. Note the priest’s door. Right: The south transept with an unusual configuration of four cusped lancet windows. They are rather like a transitional design between Early English and Decorated styles. This configuration is repeated on the east side; which fits with the supposed date of 1300. To the left you can see the large perpendicular style window that has intruded into the now-blocked south door below. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west front. It is an odd sight and you need to remember that this is where most parish churches have their towers. The profile is rectangular - again unusual - and is crenellated. The window is in Decorated style. The lower part is clearly later and I am guessing that it dates from the 1862 restoration. Right: This is perhaps the real gem of Stoke-sub-Hamdon. It is a representation of George and the Dragon and located above one of the Norman windows just to the west of the north porch. Notice the way the dragon’s long tail loops round George’s feet and up his back. The dragon’s tongue seems to have captured a sword but perhaps the saint is holding a spear in one hand and a sword or dagger in his other - a feat of arms indeed! Lesley Strutt challenged me to spot the possible Anglo-Saxon connection and I unhesitatingly answered that it is this sculpture. Interestingly, and unknown to me, Pevsner, said the same. I wondered if it had been recovered from an earlier Anglo-Saxon building but it would be a little coincidental that the tail just happened to fit the Norman window profile! This is an early Norman church so we must speculate that the mason was just not up to speed with modern art! What a treasure this is. It’s worth the visit on its own. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The George and Dragon window. Centre: This Norman window has just survived the incursion of the south transept. Right: Another Norman window. As you can see, all of the decorations are distinctly Norman with cables, chevrons and the like, but no two are the same. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Stoke sub Hamdon Tympanum. At the top three birds are pecking at a Tree of Life. At ground level Sagittarius is apparently aiming his arrow at Leo. We know that the mason meant this to be Sagittarius because he has carved it on the left. Leo has his name carved a little less conspicuously below his body. This mason was no artist. We can forgive him, perhaps, for his total ignorance of the anatomy of a lion but we can’t really excuse the Lamb of God looking like something from Crufts. And what on earth is the benighted animal doing with his left front leg? There is speculation that Sagittarius is King Stephen and Leo is Geoffrey of Anjou from whom Stephen usurped the English throne. The problem is that Sagittarius is seen contending with a lion in several other places: Kencott (Oxon), The Rock of Cashel (Ireland) and Augsburg (Germany) are just ones I know of. In other places he fights dragons (see Adel in Yorks) and in the Bestiary he is reputed to fight savages clad in lion skins. And would our mason who can’t even carve a sheep be so sophisticated as to make a political point? It is also worth mentioning that “Leo” is Latin for “Lion”. So our (presumably illiterate) mason might well have just been telling the world what it was that he was carving as there were no other clues! I’m sorry to be a killjoy (and I am sure that there are plenty who will want to believe the more esoteric explanation) but the simplest explanation is usually the best. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Sagittarius and his inscription - which is also gives us a fascinating look at twelfth century letter forms. Crude as the Sagittarius carving is, he does seem to have a Norman helmet which would give some support to the King Stephen proponents. He appears also in very weird form at Beckford in Worcestershire - alone on this occasion - and here too there is speculation that he represents King Stephen. Right: Scrolled capital on the south doorway. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The east shaft of the doorway. Centre: The western shaft with a pattern of scales. Right: The north porch and doorway. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south doorway. Note the similarities with the north doorway. Right: The Norman font. The raised cable and diamond designs are very unusual. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The interior looking towards the east end. Note the hefty transept arches to left and right. Note the various bits of wall painting, including above the chancel arch. Right: The Norman chancel arch with three courses of decoration. There was a rood screen until it fell in 1795. More recently it has been replaced by a rude screen to the left.... |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking through the chancel arch towards the west end with its Decorated style window. Right: The southern capitals of the chancel arch. Note that the middle shaft has the same pattern of scales as is seen on the north and south doorways. The scroll capitals are very nicely executed. Indeed, the whole arch is in very fine condition. It has been rebuilt and restored so it’s hard to know whether any or all of it is recut. |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: The south wall of the chancel. The only original window is the small one to the left of the (screened) priest’s door. Note the quite fine work on the left hand window. There are nice little shafts either side of the splay and the masons have gone to some trouble to create and attractive window rebate. Right: The view to the west. The west window looks a little bit squat as if its bottom has been chopped off. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: The various wall paintings are, according to the Church Guide, seventeenth century. These examples are above the chancel arch. Right: The south nave wall. To the right is a small small stone screen and beyond it the base of the tower. This started life as the north transept but the tower was subsequently built over it. Note the merest fragment of a Norman window close to the organ. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west end of the south transept. The windows have the simplicity of Early English but the rear arch is quite sophisticated. Right: This is an extraordinarily deep squints that connects north transepts to the chancel. In the background you can see an eighteenth century funerary slab in the a corner of the chancel. This begs the question I often have: how useful were squints and do we really understand them? Why was this one not looking towards the altar, I wonder? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Just above the south squint is this fascinating carving. For the life of me I can’t tell what it is. It was brought here in 1871 from the Abbey Church at Montacute. Centre: In the south transept is this effigy that is believed to be the transept’s founder, Robert de Monckton. Right: At the north east of the chancel is the canopied tomb of Thomas Strode (d.1595). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

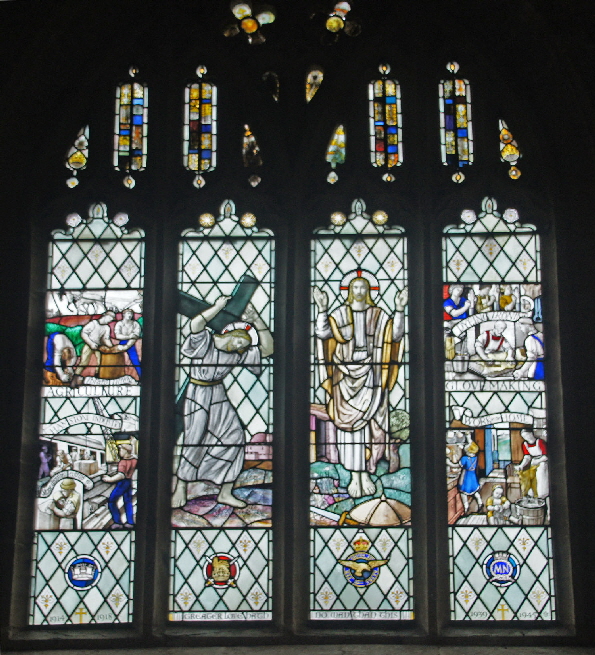

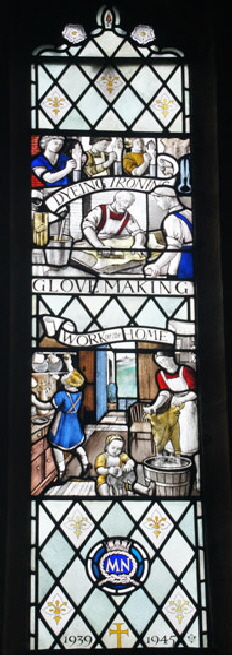

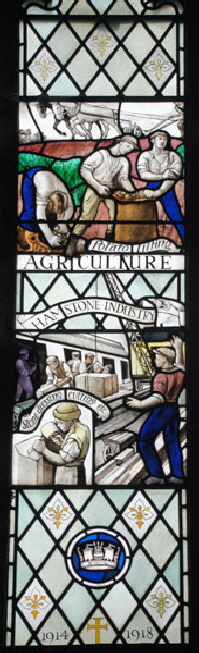

Left: The east window is fourteenth century in perpendicular style. It is post-war. The symbols at the bottom are of the Royal Navy, Army, Royal Airforce and Merchant Navy - the latter all too often forgotten in accounts of the conflict. The two outer panels show the local Stoke sub Hamdon industries. Centre: The right hand panel shows the craft of glove-making which still exists in the village and - rather charmingly - “work in the home”! Look at Mum washing her clothes in a wooden tub! Thank God for Hotpoint. Right: Here we have agriculture - still using horse power - and the quarrying of Ham Stone. I must say, I loved this window and so will history students in the centuries to come. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: this window dates only from 1881 and is dedicated to the memory of the vicar’s wife. Centre: Lesley Strutt pointed out the unusual image of a black man in the right hand panel. Of course, black people were not unknown in nineteenth century Britain - nearby Bristol is still infamous for its associations with the slave trade - but it is unusual to see one portrayed in Victorian England. This surely has to be a very calculated statement by the family members that commissioned it. Right: The north transept has mediaeval glass showing St Denys, patron saint of France and dating from 1430. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three Norman Corbels. The rest are of geometric designs. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stoke sub Hamdon has attracted some memorable quotes, which gives you a measure of the impact it makes. Sir Gilbert Scott (architect and church restorer) in 1856: “One of the most interesting churches I have seen: containing portions of extreme beauty” Nikolaus Pevsner: “An uncommonly varied assortment of parts and motifs, all overlapping each other. In pleasant disorder” (!) Robert Harbison (in the Shell Guide to English Parish Churches: “A lively jumble with wonderful relics preserved in its walls like flies in amber”.” Nigel and Mary Kerr (in “A Guide to Norman Sites in Britain”): “...what a lot this beautiful and cherished church has to offer” Lionel Wall (!): “It is a car boot sale of a church. I don’t think you can move three feet in or around it without finding something of interest - or something that has you scratching your head”. I can just about forgive Simon Jenkins for giving it only two stars, although I think maybe it proves the dangers of subjective “ratings systems”. What is absolutely bizarre is that the new edition of “Betjeman’s Best British Churches” (which has little to do with the original) ignores it altogether despite describing seventy-six others in Somerset including its worthy but infinitely less interesting neighbour at Norton sub Hamdon! Harris’s excellent “Guide to Churches and Cathedrals misses it out too. I can only assume the editors got lost! More of that in Footnote 3. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the time of my visit in 2015 the church was kept locked. Fortunately, however, the church displayed telephone numbers for people who held keys and I was fortunate that Lesley Strutt not only appeared within ten minutes but also spent a long period (on a rather grey day) showing me all of the church’s many treasures. Lesley is also the author of the Church Guide. She explained to me that even in this rural part of Somerset they have had to endure misuse of the church. At the time of my writing this update in 2022, the church is shown by the Keyholder app as being “open”. I have to be honest and say that conducted tours of parish churches by churchwardens and keyholders are a hit or miss experience. All are well-intentioned delightful people and usually eager to point out the church’s finer points, some of which you could not otherwise be aware of. Some, however, are simply a distraction and want you out of there as soon as possible! Lesley, however, was a delight. She had studied every inch of the church and was able to point out many things that I would have missed. She joins the lady who showed me around Heddon-on-the-Wall Church in Northumbria in my pantheon. My heartfelt thanks and admiration to her. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 3 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This church is hard to find. I was quite serious in suggesting that some Gazetteer editors may have been unable to find it. That’s more charitable than suggesting criminal lack of discernment. I put “Stoke sub Hamdon” “Church Lane” into my satnav and it took me to the church at Norton sub Hamdon. Before you chortle at the shortcomings of satnavs I should point out that he church notice-board at St Mary’s Norton sub Hamdon bears the words “St Mary, Stoke sub Hamdon”! Looking at Google Maps it also looks as if it IS a part of Stoke and not Norton. Even the dedication of the two churches is the same if you ignore the tautological “the Virgin” bit. Weird or what? So do your homework on this one before you sally forth. It would be daft to see one and not the other as they are very close. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||