|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Certainly this was a church of prestigious proportions, although the Church Guide suggests that the tower was complete some fifteen to twenty years after the rest of the church, the masons having moved to Canterbury in the interim to assist in rebuilding after a disastrous fire. One is struck by the puniness of the aisles compared with the rest of the church. The Church Guide is, I think, exaggerating when it says that aisles in Norman churches were not very common but it is certainly unusual that they were not subsequently widened. Originally they had no windows. Unusually, the south doorway has been filled in, leaving a slightly later north door that has a degree of decoration that suggests it was meant to be used. This is contrary to the norm where the north door was less favoured due to a belief that the north was “The Devil’s Side”. This church, however, was built by a monastery so it is likely that they rejected the old superstitions about the north side. To see more on this topic please see my account of Church Hanborough (Oxfordshire). The church is constructed of flint but the stone dressings are of Caen stone as is quite common in this area where Normandy was but a short cross-Channel voyage away. There are reminders of the town’s maritime heritage inside the church in the form of quite elaborate graffiti of ships carved upon the pillars. Sadly it was impossible to pick out the detail from the photographs I took. There are two fine Norman doorways here. The earlier and more spectacular is the west doorway. It has courses of the impenetrable decorative carvings so dear to the hearts of the devotee of Romanesque sculpture. The carved area is enclosed within a gable-shaped outline that replaces the more conventional semi-circular tympanum framework. The north door is better preserved, protected as it is by a porch, but its style is perhaps thirty or forty years later. There are quite sophisticated decorative courses. Inside the church one is immediately impressed by the height of the aisle arcades. They are wondrously symmetrical. The chancel still has its Norman windows throughout. Its length and loftiness can usefully be compared with the small vaulted chancels that can be seen at such places as Tickencote in Rutland and Devizes in Wiltshire. It has none of their intimacy. Both tower and chancel arches are of monumental proportions.. The original clerestory is also very interesting. It has pairs of bifora openings that are blind - that is, unglazed, alternating with single glazed windows. I think that these bifora were likely to have been unglazed from the beginning. On the south side the infill has been faced with a rather unfortunate concrete rendering but on the north side is seemingly filled with the original flint rubble. Pevsner did not agree that the tower was slightly later than the rest of the church as the Church Guide contends. He cited the external arcading as evidence of this but also that the tower arch was later than the chancel arch - concluding that it had been altered. Yet my own observation is that the westernmost clerestory arch on the south side has been ever so slightly cut off which suggests that the tower was indeed later and that the tower arch is at it was originally and contemporary with the tower. The later date would also be consistent with the later north door. Pevsner observed that the stumpy tower somewhat marred the church visually. |

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

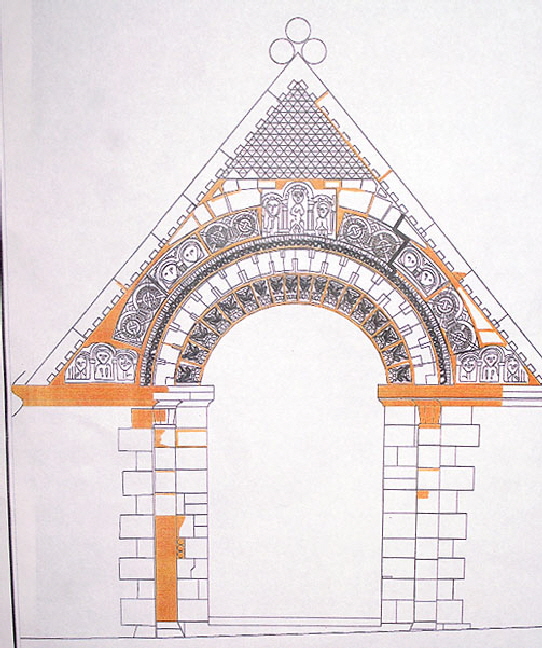

Left: The west end of the tower. Essentially it is all Norman but has been disfigured a little by the need for two phases of buttressing. Right: The west doorway is the treasure of this church. The modern porch protects if from further weathering but the gable shape of the masonry invites us to speculate as to whether there was some also sort of porch here originally. It is an unusual composition in every way. Note the three figures at the apex of the gable and two more clusters of figures at the terminations of the decorative courses. The capitals, by contrast, are very plain. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: The three figures at the apex of the west door. We must imagine the central figure to be Christ with apostles at each side but they are remarkably crude. Right: A further cluster of three figures at the termination of the decoration on the right side of the west door. They are enclosed in Romanesque-style arcading. All of these figures contrast with the much higher quality of the decorative courses. Very simply, we are surely seeing here that some of the masons - builders really - were quite capable of carving stylised decoration with the primitive tools available to them but that asking them to carve human forms took them into a world of art that was a step too far. |

|

|

||||

|

Left: There are four decorative courses around the arch plus a geometric design filling the space between arch and gable. Right: The predominant pattern on the outer course of the arch is this pair of concentric circles intertwined with a saltire cross. |

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: The inner course of carving was a repetitive stylised pattern. Right: This, by way of contrast, is the later north door. It is more stylised in its decoration and, it must be said, less interesting! All of the decorative courses are fairly run-of-the-mill for the period but the lozenge shapes on the outsides course do have small inset motifs. Despite the superficially greater sophistication of this piece you can see that the outside course is very irregular in its execution. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: detail of the north doorway. Note that the chevron moulding is also quite irregular. Right: This design inside one of the lozenges is, I think, meant to represent Plato’s World Soul aka “Solomon’s Knot” (see Mary Curtis Webb) but the masons have botched it by not properly executing the interlinking of the two “circles”. This adds to the sense that the masons here were out of their depth with decorative sculpture. If this device was intended to have philosophical meaning then that idea would surely have come from St Martin’s Monastery in Dover but getting the masons to fathom how to carve it on site was surely another matter. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another geometric design. This is quite common in Romanesque sculpture but I don’t know what is represents. Right: The north side has this rather odd human-like face. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The noble chancel arch with the impressively-dimensioned chancel beyond. Right: Looking towards the west end. Note the loftiness of the arcades and that they are symmetrical. The tower arch is also impressive. Why, though, is it pointed when all the other arches in the church are round? If it were original then that might support the notion that the tower was built after the rest of the church. I suspect, however, that the arch profile was changed much later to accommodate the organ! Note the way a string course progresses from around the tops of the arcades to the tower arch. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the north east of the church. The arches are of Caen stone, making a very clear delineation between arcade and clerestory. Note the deep splays visible for the north aisle windows, suggesting Norman provenance. But the Church Guide says that all of the aisle windows were later additions. The east window is an early English style lancet but is Victorian. Right: The decoration around the arcades is restrained and looks all the more sophisticated for it. This masonry is beautifully executed and in stark contrast to the shortcomings of the two Norman doorways. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end of the south aisle, this time with what looks like and original Norman window but which is not.. Right Upper: The chancel. There is a wonderful rhythmic quality to its proportions and windows. Unchanged Norman east windows are a great rarity. The uppermost window is, however, nineteenth century. Right Lower: One of the arcade capitals. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two pictures of arcade capitals that prove, if nothing else, how challenging photography can be in churches! Both these carvings are in the nature of “green” creatures spewing ribbons (as opposed to foliage) from their mouths. The creature on the left has more examples of the the circular design intertwined with saltire crosses as seen on the north doorway. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another capital. Note in the central panel a pair of birds. Right: A pair of perplexed faces. The one on the left seems to have been gouging his own head. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: It is not unusual for our coastal churches to have memorials of shipwrecks, drownings and other maritime catastrophes. This window commemorates one that is recent enough to still resonate with many of us: the “Herald of Free Enterprise” disaster at Zeebrugge on 6 March 1987 which claimed the lives of three mariners of the village and one hundred and eighty seven other passengers and crew. Those of us alive at the time will never forget the horror. Right: A short section of the north clerestory. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A length of the south clerestory. Most of the arches are “blind” and filled (now) with grim modern material. Vandalism really. The masonry above is a later parapet and I assume the corbels are likewise. Were there decorative Norman corbels before? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The strange discontinuity at the west end of the south clerestory that, in my view, supports the Church Guide’s belief that the tower was added later in the Norman era. Right: The church from the south, emphasising the over-mighty tower. Note the apparent line of quoin stones in the middle of the top stage that are a bit of a mystery. Note also the legend picked out in brick on lowest pat of the tower that proclaims major work carried out in 1773. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The church displays this really useful drawing of the west door as it would have appeared before it became weathered. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - Kent |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kent was a kingdom in its own right after the invasion of the Germanic tribes following the departure of the Romans. Exactly which of the tribes settled in Kent is disputed even now. It seems almost certain that the Jutes settled here but their own origins are far from certain. It is possible that, as their name implies, they were from that part of modern Denmark we now call Jutland but many historians dispute this and believe they were associated with the “Franks” who, of course, gave their name to modern France. Throughout English history even to this day there are subtle differences in the way Kent is administered compared with other counties. As the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms consolidated through conquest Kent was somewhat dwarfed but managed to cling to its identity. Its kings never challenged for the unofficial title of “Bretwalda” that implied (but was not always respected) overlordship of the other kingdoms: that was a title enjoyed at various times by Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex. Kent at various times paid tribute to Northumbria, was conquered by Mercia before being subsumed by the hegemony of Wessex. Certainly Flanking the Thames Estuary it also was one of the first ports of call for Danish raiders and later for invading Danish armies. Like all of “Anglo-Saxon” history, Kent’s early story is complex and not a little opaque. It is one of that select group of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, however, whose names live on in the modern English county structure. As well as Kent we still have Essex (the East Saxons), Sussex (the South Saxons) and Northumberland. We also still have the geographical region of East Anglia (split between the North Folk and the South Folk). Yet, ironically, we have lost both Mercia and Wessex (despite the best efforts of Thomas Hardy!) as modern locations. Many Welsh kingdoms (such as Powys and Gwynedd) also survive and the Scottish kingdom of Strathclyde manages to live on in much the same way as East Anglia. If I have missed out your favourite Anglo-Saxon locality please don’t complain. This is not meant to be a comprehensive list! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||