|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

three wool magnates in Long Melford alone. If you want an idea of how lucrative the wool trade was then conjure with this: Lavenham five miles away was by the fifteenth century paying more tax than York or Lincoln and by 1524, with a population of about 2000, was the fourteenth richest town in England. What was here before? We don’t really know except that the piers of the five westernmost bays of the arcades are of the fourteenth century. If this signals the extent of the original nave then it was already a church of some substance, making Clopton’s rebuilding all the more hubristic. The nave now has seven bays. the aisles and clerestory are perfectly integrated with the nave: each bay has a corresponding two Perpendicular style windows in each of the aisles and two smaller but still substantial windows in the clerestory. The overall effect externally is of a massive glass wall interspersed with a bit of masonry. The proportioning is perfect. The clerestory is topped by fashionable battlementing of the most fashionable kind and of the highest quality. The aisle , however, are not adorned in that way: the patrons and the masons clearly understood the aesthetic value of allowing the eye to be drawn from aisle to clerestory without interruption. Like most churches in Suffolk and neighbouring Norfolk, the outer facing of the church is mainly of knapped flint. This is because Suffolk lacks quarries for dressed stone and the cost of carting stone in medieval days was monstrously high. LF Salzman in his “Building in England down to 1540” calculated that typically at a distance of only twelve miles the cost of carriage exceeded the cost of the stone. You might think that Clopton’s wealth would have allowed him to import stone from elsewhere but by the fifteenth century the East Anglian counties had perfected the art of using locally-available flint to face their churches and it is hard to counter an argument that this is a more attractive effect than that of dressed stone. That said, there is more stone in this church than in most in East Anglia and amongst other things it is used to good effect in the singularly attractive “flushwork” effect employed at many flint churches: that is the use of dressed stone inlaid into a flint finish to produce decorative patterns, lettering or monograms. Returning to the interior the chancel occupies a further two bays. The Church Guide rightly designates if the “Sanctuary” and with good cause. Clopton and his cronies were not simply providing a magnificent setting for parish worship. The chancel is beset by chapels. To the north are the Clopton Chapel and beyond it to the east the Clopton Chantry Chapel. To the south is the Martyn Chapel built by another benefactor family. Most remarkable of all is the Lady Chapel which is situated east of the chancel and which can be accessed only from the churchyard. Both its position and its great size make it extraordinary. A downside of the church’s architectural unity is that there are no ancient nooks and crannies to be searched for. There are no Norman remnants here; no Early English lancets. This is an adorned work of the fifteenth century. Once we have admired the scope and beautiful execution of the work it is to its furnishings we must turn to hold our interest. Foremost amongst these, perhaps, is an extraordinary collection of church brasses, memorials to the wool merchants of Melford and providing an invaluable guide to the costume of the period. There are carved friezes, rich funerary monuments, painted ceilings and a host of other things to feats upon: all, of course, of the highest quality. |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the east. The arcades - with nine bays is all - march eastwards almost, it feels, to the horizon. Look at the arcades, the clerestory, the aisle walls. What proportion of what we see is actually stone as opposed to glass and space? What would a Norman mason, say, have made of this? His walls would have been of great thickness, his piers of monumental proportions, his windows tiny. At Long Melford the building seems to float with only a skeleton of masonry to support it. There is no chancel arch, no sign there was ever a rood screen. Nothing was allowed to interrupt the awe-inducing view from east to west. Right: The chancel looks almost modest. The east window is small compared with many. Cathedral-like, the clerestory embraces chancel as well as nave to leave an uninterrupted roofline from west to east. It is the inordinate height of this chancel that makes it appear smaller than it is. Note the Clopton Chapels to the left and the Martyn Chapel to the right. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

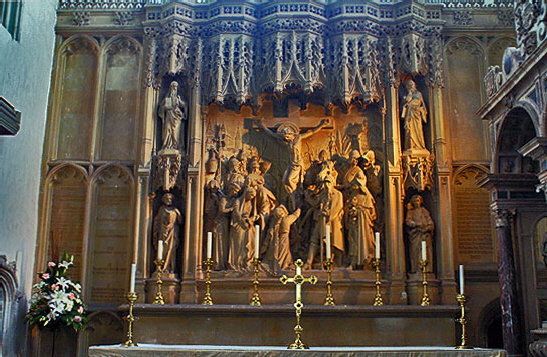

Left: The reredos dates from 1879. Right: The view west along the nave. Amongst the many thought-provoking things about this church is the configuration of the west end. Gone is the old notion of a low tower arch leading to a dusty tower room with a wooden ceiling pierced by bell ropes. As you can see, there is a modern low wall and doorway but this low profile ensures light through from a double west window. The tower itself, however, is a little bit of an oddity. The original one was destroyed in 1725. and was replaced by one made of brick. Brick...? Clopton and his mates must have been turning in their well-appointed graves! I have already noted, however, that stone would have been a very expensive commodity in Suffolk. Presumably no wealthy benefactor was now available and the village was economically constrained to use the much cheaper brick. It must have looked an abomination. In 1903, however, the tower was - mercifully - enclosed with flint work that gives the church the architectural harmony that prevails today. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

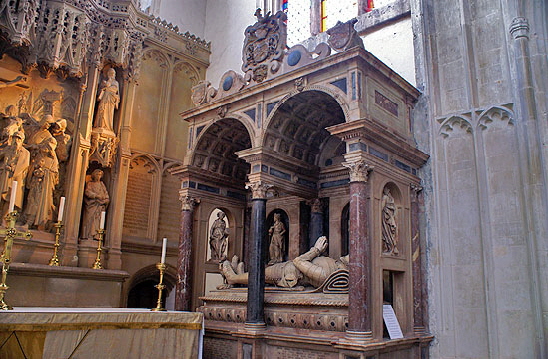

Left: The clerestory from inside the nave. Right: Close to the altar, this is the tomb of Sir William Cordell (1522-81) who was Speaker of the House of Commons under the Roman Catholic Mary I and Master of the Rolls under the Protestant Elizabeth I. One can only imagine the careful line he must have trod to be politically prominent two such strong-willed and religiously polarised figures. Elizabeth, however, did not include him in her Privy Council despite his high office.. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The roof of the Clopton Chantry Chapel. Right: The Clopton Chantry Chapel is enriched by these elaborate blind niches and by a painted roof and frieze. The frieze is adorned with texts in early English from the poetry of John Lydgate, notably “The Testament of John Lydgate” - see footnote below. |

|

|

||||||

|

Two sections of the Clopton Chantry Chapel frieze. In between the texts are vine scrolls. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: The tomb of Sir William Clopton, the father of the founder in the Clopton Chapel. Right: The Clopton Chantry Chapel which adjoins the Clopton Chapel. It is very easy to confuse the two - especially when, as I am doing - you are trying to remember a church you visited nine years before! Note the now illegible wall painting. Here priests or monks would have been praying for the immortal souls of the Clopton family. What with that and having rebuilt the church they must have felt that they had done as much as any rich family could to speed their passage through the dreaded purgatory. |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

The floor brasses Roger Martyn (1526-1615) and his two wives. The brasses here can tell the student much about the costumer of the day so I reproduce the three individual figures as close-ups (with some loss of resolution, I fear). Both wives wear farthingales to fill out their dresses. Roger Martin was a very interesting man - and I’m not just talking about what was for the time his remarkable longevity. In the time of Mary I he was churchwarden here and helped to re-establish the revival of Catholicism. Mary’s reign was short-lived, however, and left Roger seriously compromised under her successor, Elizabeth. He was now a “recusant” - one who refuses Anglican rites - a precarious status indeed. He was fined the enormous sum of £200. He was imprisoned twice for harbouring Catholic priests - often a capital offence. He lived to tell the tale, however, and died peacefully. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Richard Martyn (1559-1624). Richard was the son of Roger (above) and was also a recusant. He might not have enjoyed quite the long life of his father but he managed to have three wives to his father’s two! Other Pictures: I didn’t record the names of these figures but you can see what a fine collection the church has. I particularly like the lady second left and her magnificently OTT head wear. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top: The Richard Martin brasses. You can see from this picture that the brasses of Roger Martin and Family to their right are indeed set in a blue stone and not - as even I had wondered - a trick of digital photography processing. Above Left: One of the small sub-brasses from the Roger Martin brasses - presumably his children. There are two of these but he did live a long time and have two wives! Above Centre: A sub-brass from the Roger Martin group. Just two here, one a young girl. Right: This picture down the north aisle towards the west shows how many brasses this church once had. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The font is also fifteenth century in Perpendicular style and is surmounted by this large decorative cover. These large covers are very characteristic of Suffolk churches. For a real humdinger see Ufford. Centre and Right: Two of the nice carved corbels that help support the clerestory roof. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: I loved this little Millennium stained glass tribute to the local Brownie pack. Just look at that lovely toadstool. It’s a fly agaric, though, and they’re poisonous! The owls a bit of a curiosity. The eyes are almond shaped rather than the usual fixed round-eyed stare of an owl. So my guess is that this is a deliberate pun on the fact that Brownie pack leaders are designated “Brown Owl”. Cute! Right: Fragments of mediaeval glass. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A delightful surviving mediaeval glass roundel showing three hares - sharing three ears! You can see another one at Widecombe-in-the-Moor in Devon as a roof boss. In that part of the world they are known as “Tinners Rabbits”. As with so many icons of this kind, however, Christianity does not have it to itself. It appears on cave paintings in China in the sixth and seventh centuries and has been seen in countries as far afield as Persia (Iran) and Turkmenistan on manuscripts, pottery and metal plates amongst other things. Nobody knows “what it means” although that doesn’t stop much learned explanation and patent hogwash. In the Far East it may be a good luck symbol. In a Christian church some say it characterises the Holy Trinity. As Long Melford Church is dedicated to the Holy Trinity that seems very plausible. Others say that the hare was once believed to be able to produce offspring without involving sex and that this symbolises the Virgin Birth. You may find that a remarkably inventive explanation! Like the Green Man motif, it is too distinctive for us to believe that it appeared spontaneously in many countries. Such imagery clearly travelled and was “re-interpreted” as it did so. There was no book to consult. Even in England it is eminently possible that artists in glass, stone and wood had quite different ideas of what they were representing. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Lady Chapel really is - I know I use this word too much - remarkable. The chapel itself is arcaded and it has an ambulatory around its entire perimeter. Here we are looking towards the west end of the inner chapel. No expense has been spared in the quality of the stonework and the frieze of Perpendicular style blind arcading shows that no expense was spared. Right: This is the east end of the inner chapel and the only wall that is not open to the ambulatory. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Lady Chapel ambulatory south side. Right: The woodwork at Long Melford is very fine as is everything about this church. This timber in the Lady Chapel roof shows vine scroll carving similar to that in the Chantry Chapel. What, though, is that hand doing that is emerging to the right? Is it cutting the vine? |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

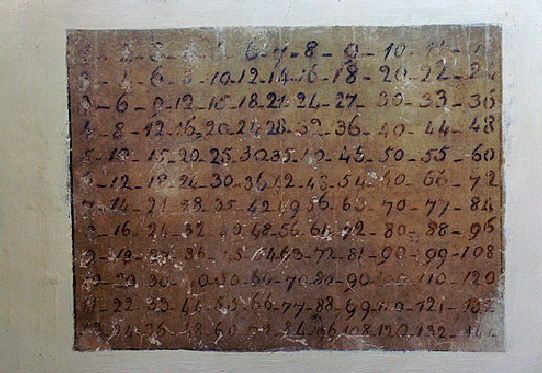

Left: In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Lady Chapel suffered the indignity of being used as a school room. This is is a multiplication table that has survived from that period. Right: The Lady Chapel from the south west, Note the lovely flushwork. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A section of the clerestory. One of the unique features of Long Melford Church is the continuous flushwork frieze of text. Note also the cornice frieze of fleuron carvings and the flushwork shield on the battlements. Think about all of these stone pieces being individually carved and with the utmost accuracy and you begin to understand that this church must have cost a fortune. No expense was spared, it seems. Right: The church from the south east.. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Perhaps only this picture of the east end really captures the sheer magnificence of this church. The Lady Chapel shows a triple face to the world and the flushwork is of breathtaking complexity. It really is a building placed at the end of another magnificent building. It could easily be a mediaeval town hall. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - John Lydgate |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

I am indebted to Adrian Habgood-Rose who kindly corrected my initial mis-description of the texts in the Clopton Chapel as “latin prayers”. I’d never heard of John Lydgate, I confess. Lydgate (1370-1451) was a monk who lived in Lidgate near Haverhill in Suffolk. It is worth mentioning that surnames were not at all common in mediaeval times and that they were generally associated with a person’s occupation or home town - as with John Lydgate. A self-confessed sinner in his early life, Lydgate became a Benedictine monk at Bury St Edmunds and had literary ambitions. He was patronised by Henrys IV, V and VI as well as other members of the aristocracy. Those three Henrys were similar only in their names (a usurper, a military hero, and a usurped scholar respectively, so this was quite remarkable! He was a poet and writer of romances and fables. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||