|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A second stage was added to the tower later but also before the Conquest. It is the tower that is the most striking survivor. It has an impressive tower arch, original pre-Conquest windows and a well-hidden Anglo-Saxon graffito of the legend of Ragnorok to leave what I called in the Visitors Book “one of the most interesting vestries in England”! There are no overtly Norman features in the church but alterations were made during the late twelfth century in the Transitional style when shallow two-bay aisles were added to both the north and south sides. In both cases the arches are pointed and with dogtooth decoration that still nods towards Norman practice. The arcades are, however subtly different in terms of the profiles of the piers and arches, of the capitals and of the decoration. This suggests that the north aisle was built first and that the south aisle followed very quickly if not immediately. The south doorway that penetrates the south aisle has a round arch with a single, almost apologetic, course of thin chevron moulding in keeping with the architectural schizophrenia of the Transitional style. Both aisles were extended eastward by an extra bay in the late thirteenth century. At that point the chancel was rebuilt on a grand scale. It is worth looking at the picture above to reflect upon the way this church grew. The extent of the original church was only the base of the tower plus the nave as far as the first two windows beyond the porch, There would have been a chancel or apse that would probably have extended no further than the aisle. The new aisles would have then extended the church laterally. Then - bang! The church is extended to about double its length by the lengthening of the aisles and the huge new chancel. Note the height of the chancel as well as its length. The roofline of the nave was dropped very slightly and then extended in one long sweep from tower to chancel. A belfry stage was added to the tower in the fifteenth century. It was reported that by 1582 the chancel was decaying. This was rather soon after its building! I have found no description of the remedy that was applied although the buttressing is very business-like. The chancel windows are very imposing in size and rectangular profiles are not usual in the early fourteenth century. Are they original? I think they probably are. The tracery looks authentic and I am struck by th fact that the clerestory windows are also rectangular. So - back to that south door! It was only after studying the photographs the same evening that it became patently obvious that the principal decorative motif is of four overlapping appearances of the circle interlaced with arcs design. The overlapping is what makes them easy to miss. There are other decorative desings, one of which I am sure is a St Brigid’s Cross. I can’t keep writing about these so please refer to “The Late Mary Curtis Webb” to find out more about the circle interlaced with arcs and Stillingfleet for St Brigid’s Cross. So what are the implications for the door’s age? Well, I know of no appearance of the circle with arcs imagery beyond the Norman period in England. The doorway itself is definitely Transitional. I think we can safely say the original door was then around 1180 or 1190 and not thirteenth century as other have suggested - generally, I think indulging in a bit of that pandemic “Pevsnermustberightis”! Forget the issue of “restoration”. It is quite clear that this is the case of restoration and not replacement and a lot of the decoration looks quite ancient and un restored. It is not stretching it to say that the door decoration (as opposed to the planking) is effectively original - and of great significance. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

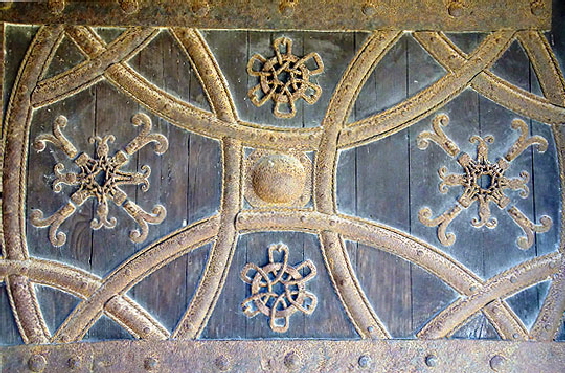

Left: The intriguing south door. Horizontal iron straps divide into four zones, There are two complete and two partial circles with arcs images - four in all. Down the centre line of the door is a recurring circle interlaced with six arcs. There are four other pairs of designs that may or may not have hidden meanings. Right Above: The second panel from the top. Right Lower: A close up of one of the designs. This is a considerable feat of ironwork with strands of iron forming a complex design. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The circle interlaced with six arcs. This motif appears eight times. Mary Webb found a picture of it in Lambert of St Omer’s “Liber Floridus” (a mediaeval encyclopedia) of 1120. I am unable to decipher the script but Ghent University Library describe it as “Ages of the World”. Right: I believe this to be St Brigid’s Cross which also appears four times on the ironwork of the door at Stillingfleet Church. It was used as a kind of Christian good luck charm - although it is widely believed that St Brigid was a character contrived from a pagan! |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: After all the onscure symbolism this is one of a pair of what are clearly Christian crosses - albeit damaged in this case. Right: The door knocker that might also be the sanctuary knocker. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east and its imposing window. There is no chancel arch nor any sign of a rood loft yet it is known that a rood screen was installed fifteenth century. Perhaps all signs of it were removed at a later phase of restoration. Ditto the chancel arch. Right: Looking east. Note the nearest bays of the arcades which were installed when the aisles were extended. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle. The eastward extension is very apparent both in terms of the arch and of the Decorated style windows. Right: The north aisle. Compared with the south aisle the dogtooth moulding on the arches is slightly less dense. The moulding of the arches is slightly less sophisticated and the the capitals owe more to the Norman period. The clerestory is also somewhat shallower. It is then likely to be slightly earlier of the two aisles. Note, however, that the aisle windows were replaced in the sixteenth century. The aisles penetrate walls of the original Anglo-Saxon nave. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. Right: The tracery of the east window. Something is clearly not quite right here and the glass below the tracery has clearly been replaced. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

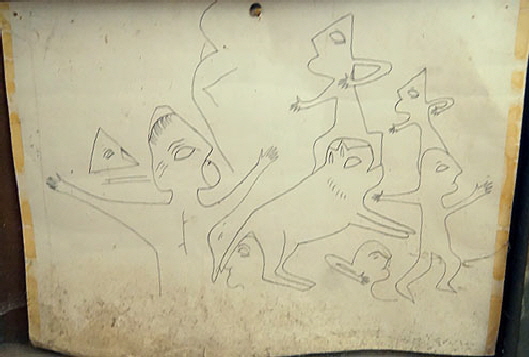

Left: The north side of the tower arch. The construction was said by Taylor & Taylor in their three volume definitive work “Anglo-Saxon Architecture” to be unique, As you can see, there are two courses of strip work but inside these are horizontal courses of masonry. The simplicity of the impost blocks is typical Anglo-Saxon work. Right: This remarkable piece of Anglo-Saxon graffiti is near the floor within the base of the tower. I have seen it described as “Ragnorok”, depicting the Viking view of the Apocalypse but this is, I am afraid, fantasy. Others suggest that it looks much more like a depiction of a boar hunt. Rita Wood has identified seven other example of this imagery in England but, again, this image bears little resemblance. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This drawing in the church shows what the camera struggles to show. The “boar” has no tusk and is probably a dog. There is not the slightest reason to connect it to the monster-laden imagery of Ragnorok! Right: The carving is at ground level of the tower on the north side and protected by a small door. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north window of the tower is Anglo-Saxon and splayed inside and out. Taylor & Taylor point out that the interior splays of the ground floor window are carefully constructed by voussoirs of stone whereas their on the outside they are headed by large stones with the shape of the arch cut out. They also say that Skipwith is the most northerly example of double-splayed windows in England other than Jarrow in Northumberland. Centre: This is the south side of the tower and you can see that the lower of the two windows indeed has a head carved from a single stone. Taylor & Taylor see this as being unusual and they contrast it with the later second Anglo-Stage that has windows with voussoir heads inside and out as you can see from this picture. They conclude there is a possibility that the lower stage windows were originally splayed inside only. The small window was probably to provide extra light to a particular part of the upper chamber. Right: The tower from the west. The lower window is a later insertion. |

|

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: The tower arch from within the tower itself. Note again the masonry infill between the pilaster strips. Centre: The south aisle looking east. The large expansion of the church eastwards has left the aisles looking somewhat forlorn and undersized! Originally they were even smaller, reaching only the pillar to the left of this picture. I find it very surprising that the aisles were never widened. Right: Here on the north aisle wall you can see very clearly where the original Anglo-Saxon nave ended. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: Looking from the chancel to the south chapel. Centre: Above the tower arch you can see very clearly where a doorway has been filled in. This is far from being unusual on east walls of surviving Anglo-Saxon towers. It is generally believed that they gave out onto wooden galleries but none have survived. To the left of this doorway - inside the first floor - is a rectangular recess. The small window on the south side of the tower (see picture above) is clearly designed to illuminate this recess. The speculation is that it was an ornate altar but nobody is sure. I haven’t seen the first floor of the tower myself (they are always locked) but I wonder if perhaps it housed a relic that was sometimes displayed to the congregation via the lost west gallery? Just a bit of specualtion of my own! Right: The east end. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - Similar Church Doors |

|

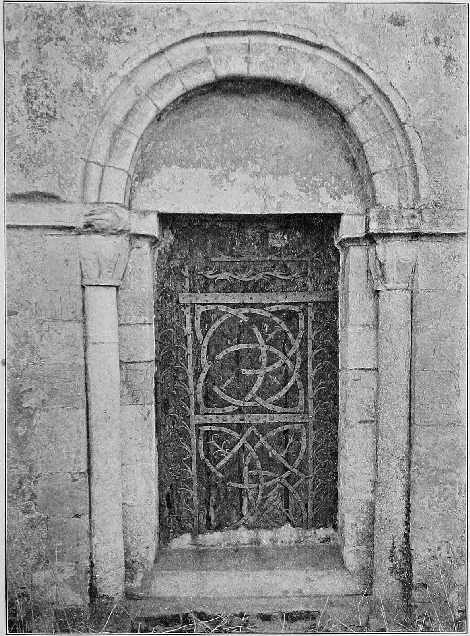

Perhaps you are sceptical about the ironwork on the door at Skipwith? We know the planks have been replaced, we are pretty confident that some of the ironwork has been restored. Maybe, you might be forgiven for thinking, that uppity Lionel has been seeing things again? Maybe it’s really just a random pattern? And who is he to go questioning the great Sir Nikolaus Pevsner anyway. If Nick says it’s Sunday, it’s Sunday. Right? Twelfth century? Not if Nicky said it was thirteenth! Well, Skipwith church door is not unique. Mary Curtis Webb herself spotted the circle with arcs motif at the little Norman church of Little Hormead in Hertfordshire. Even more interesting - and intact - are the west doors at Rochester Cathedral, no less. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The west door (top) at Rochester is not precisely the same as at Skipwith, of course, but the similarities are quite remarkable. Most obviously, the circle and interlaced arcs appears very clearly four times. Even more remarkable are the similarities in the smaller insert ironwork designs. In the picture left lower you can see two familiar motifs: what I take to be St Brigid’s Cross (enlarged in a picture right lower) and a cross with looped endings with a complex interlace design at its centre. Within the chords of the arcs is a circle interlaced by six loops. This is a much tighter design than those at Skipwith but again the similarities are unmistakable. So we have four different motifs here at Rochester and each one of them has a counterpart at Skipwith! The doorway dates from 1160. I have put the Skipwith door at maybe 1170-1190 but this was a stab in the dark. It now looks more likely to have been contemporary with this one at Rochester. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three Skipwith door motifs for comparison with Rochester. The structure of the St Brigid’s Cross motif (if indeed that is what it is) is identical in almost every detail. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Little Hormead Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Little Hormead door, as you can see, has been deteriorating for some considerable time. The design in the top panel, however, is still unmistakable, Below it is a damaged square interlaced with arcs. Mary Webb made a line drawing of this design in the porch of Northampton St Peters but there the square is lateral - that is, turned through forty five degrees compared with the Little Hormead schema. Frustratingly, we don’t have Mary’s explanation for this figure (bear in mind the book was assembled from her notes and papers after her death) but she saw it also at Rouen and we must assume that it has some sort of cosmological meaning. Ironically, Pevsner - who did not spot the similarities with Skipwith - himself dates this door at twelfth century.and the Churches Conservation Trust who now look after the church date it to 1130-1150. It is very obviously a Norman door and I hope I have convinced you that Skipwith’s door is of similar date. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||