|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions Great Kimble (Buckinghamshire) Stamford Church Trail (Various) Kingston on Soar (Nottinghamshire

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Romanesque style incorporated aisles separated from the nave by arcades and in most cases a semi-circular apse. Of the church we see today, only the chancel and the base of the tower remain from the Anglo-Saxon era. There were actually two churches here built in a line with each other and separated by a very short distance. The chancel we see today was the entirety of the first of those churches. There was, in fact, little about it that was Romanesque. However, Biscop commissioned a second church in AD685 , only three or four years later. That church did have aisles and occupied the space of the nave of today’s church! Just how long they co-existed adjacent to each other we do not know. We do know that by probably AD800 at the latest they were joined together through the building of what is the base of the current church tower. It was not a tower then, nor intended to become so: it was simply a bridge between the two ancient churches. If you look at the picture above the development of the site from one to two churches and then one larger one is not difficult to visualise. Probably there was a raised gallery at what is now the west end of the chancel. It was probably accessed by an external stairway through a surviving south doorway to the first floor of the tower There is increasing evidence that such galleries were commonplace in the earliest Anglo-Saxon churches including the two most famous “Mercian” Anglo-Saxon churches at Deerhurst in Gloucestershire and Brixworth in Northants. A794 saw the start of the Viking raids into Northumbria with the sack of Lindisfarne Monastery. It is believed that the monastery was destroyed by the Vikings at some point and was probably largely evacuated by the mid-9th century. In AD1072 Prior Aldwin of Winchcombe in modern Gloucestershire was inspired by St Bede’s writings to undertake the rebuilding of Jarrow Monastery before leaving to become the first prior of the magnificent new Norman monastery at Durham. His legacy in the church itself is the addition of two stages to the “bridge” between the two original churches to form a tower. The final twist to the story came in 1782 when the original Romanesque church that had become the nave had to be demolished because it was structurally unsafe. In 1866 repairs were made to the Saxon chancel and the inevitable Sir George Gilbert Scott built a new nave and a north aisle that we see today. Visiting Jarrow is a rather odd experience. The cult of Bede and the Northern Anglo-Saxon saints is very much alive here and there is even a commercial Visitor Centre - “Bede’s World” - just up the hill from the church. The nave is home to story boards and to glass cases containing fragments of Anglo-Saxon sculpture which are very illuminating for the casual visitor. There are books and pamphlets for sale in abundance and eager amateur guides at hand. There is an inescapable sense, however, that the nave is just an anteroom to the mysteries of the Anglo-Saxon chancel and tower base. It would be easy to be cynical about the commercialisation of the Anglo-Saxon religious legacy here, but this would be misplaced: this was one of the most important phases of English history and one where England perhaps led the rest of the world in scholarship. If the exhibitions fire the imaginations of children and their parents then I’m all for it! Outside, of course, there are still significant remains of Prior Aldwin’s monastery that was suppressed in 1536. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The view to the east through the Victorian nave to the Anglo-Saxon tower base and chancel beyond. Right: The view from the tower base (now the choir) to the west end. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The Anglo-Saxon chancel. Of the windows, the three tiny openings on the south side (right) are original Anglo-Saxon. The rest are Gothic, including the east window that dates from 1350. Right: The east end of the choir. There is a quadripartite groin vault and Anglo-Saxon doorways to north and south. The south door to the vesrty is still in use. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The middle one of the three south side Anglo-Saxon windows. Note the depth of the splay and, hence, of the masonry. The glass within the window was made in the monastery workshop. It was discovered during excavations of the monastery in 1972 and put here. This is the oldest glass in Western Europe. Centre: This window was by the famous artist John Piper. Piper (1903-92) was more renowned as a painter but also contributed stained glass to, amongst other churches, Aldburgh (Norfolk), Iffley (Oxfordshire) and, famously, Coventry Cathedral. Piper was a lifelong friend of poet laureate John Betjeman and they shared a love of the English church. “BB” is for Benedict Biscop and the cross represents the Jarrow Cross - see below. Right: “Bede’s Chair”. Carbon dating has established this to be between 800 and 1100 years old - so it was obviously nothing to do with Bede, but very ancient nevertheless! |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Anglo-Saxon glass. Right: The original aumbry cupboard, still in use today. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

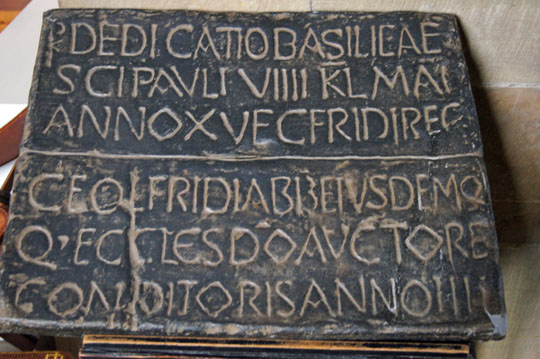

Left: I perhaps use the word “extraordinary” too often - but this is truly extraordinary. It is the original dedication stone of the church of AD 685. It reads “The dedication of the church of St Paul on 23rd April in the fifteenth year of King Ecgfrith and the fourth year of Ceolfrith Abbot and under God’s guidance founder of this same church” Right: One of a number of Anglo-Saxon fragments displayed in Jarrow Church. This one is part of a frieze showing a man and part of a beast entangled with plants stems. It dates from c8, was found during excavations and would have been on the outside of the monastic buildings. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another priceless fragment : part of the famous Jarrow Cross. It was found when the Anglo-Saxon nave was demolished in 1866. All we see here is the base of the cross and part of the inscription. In one of those occasional bits of English antiquarian insanity, the arms of the cross are in The Museum of Antiquities in Newcastle. The head has never been found. Right: One of the Romanesque features of the original church was the use of baluster shafts. They were probably used on the jambs of the arches in the church. |

|

|

The three original Anglo-Saxon windows on the south side of the chancel that once was the entirety of the church. Note that the two easternmost were “shuttered”, This believed to be because glass was not easy to manufacture in these early times. Gilbert Scott removed the shutter from the westernmost of the three. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The central of the three south chancel windows. Six pieces of stone were used to form the window, including two mini “impost blocks” between the arch and the two vertical side pieces. This is reminiscent of the design of Anglo-Saxon chancel arches (see, for example, Wittering in Cambridgeshire) and much more sophisticated than that at nearby Escomb which was probably built 10 years either side of Jarrow but which was not built by the relatively sophisticated Gallic masons of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow and is much more Celtic in design. Centre: The blocked south west door from the base of the tower. Right: The tower from the south. The doorway to the western gallery of the first church is easily visible at the first floor level. Everything above this is Norman although the bell opening are rather in the Anglo-Saxon style. We are talking here, however, of 1072 - only six years after the Conquest. Aldwin may have been building in sympathy with what was already there but it is more likely that the Norman influence on architecture had not yet spread to the north of the country. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The northern face of Jarrow Church is rather unattractive. Inappropriate Gothic style windows replace the Saxon ones. There is a blocked Anglo-Saxon doorway just to the left of the horrible rectangular window. Right: This window is in early Norman style, yet it is at the Anglo-Saxon first floor level of the tower. It appears that Aldwine replaced the south door to the west (probably by now demolished) gallery with a window |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church is surrrounded by quite substantial remains of Aldwin’s rebuilt monastery. Most of what you see here would have been an external wall. Right: A curiosity here: an Anglo-Saxon style pointed doorway. Again, I am inclined to think that this was another case of transitioning between Saxon and Norman styles |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here, on the other hand, are two obviously Norman doorways. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I don’t know whether this is a bit “cheeky” but these are photographs of two of the story boards at the Jarrow site. The drawings are by Jill Atherton. As admission here is free, I don’t think I am jeopardising anyone’s commercial interests. Left: An impression of the seventh century monastery. In the background are the two completely separate churches commissioned by Biscop. The right hand (eastern) one is today’s chancel with the three existing southern windows. The church to the left is aisled in the Romanesque style and has a western “narthex” (entrance porch). The two churches are not joined. Right: The site as it may have appeared in the eleventh century after Aldwin’s rebuilding. The two churches are joined into one and what had been a connecting building is now the base of a tower. The cloister abuts the south wall of the church. On the south side of the chancel are the living quarters and there would have been a “night stair” from the monks’ dormitory to the chancel. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - St Bede |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There is quite a cult surrounding St Bede in the north east of England. His reputation is based upon his scholarship rather than upon the evangelical qualities of the likes of SS Aidan, Wilfrid and Cuthbert. Often known as “The Venerable Bede”, as well as theological works, he wrote about history, music and science. Bede is indelibly associated with the twin monasteries where he lived for almost all of his life. He entered Monkwearmouth Monastery in AD680 at the age of only 7 years and as believed to have transferred to Jarrow when it was dedicated only seven years later. He would have been exposed to the extensive library collected by Benedict Biscop from all over Western Europe and by the first Abbot of Jarrow, Ceolfrith. His most famous work was “A History of the English Church and People” from which we gained much of our knowledge of the early church in England. bearing in mind that Biscop introduced the Benedictine Rule to England, requiring monks to remain within their monasteries, Bede would not have travelled far, although he is known to have visited Lindisfarne and probably York and Durham. This makes his scholarship all the more surprising. He was an associate of St Wilfrid and he was mentor to St Cuthbert. His importance as a scholar is acknowledged throughout western Europe. In the tenth century he became something of a cult figure when monasticism revived after the depredations of the northern invaders. Bede died at Jarrow in AD735 at the goodly age of sixty-three. In AD1020 his bones being stolen from Jarrow and re-interred with St Cuthbert at Durham, presumably a conspicuous example of the unseemly competition between monastic houses for pilgrims and their donations! He was re-interred in Durham Cathedral in 1370 where he remains. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||