|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These connection were what undoubtedly led to the church’s expansion in the thirteenth century. The chancel of the old Saxon church was remodelled and used as the base for today’s tower, its ground floor space used as a chapel. The old Saxon nave was relegated to the status of a south aisle to the Early English style nave and chancel built to its north. The chancel still has its Early English lancet windows, the triple arrangement at the east end having, for their time, unusual cusped heads. Later windows of varying styles have been inserted, as you might expect, and a belfry was added to the tower in the fifteenth century, but otherwise very little has changed here since about AD1300. It doesn’t even have electric lighting! The church has that indefinable “atmosphere” of antiquity that is so beguiling. But its treasure is not in its architecture but in its Doom painting. Readers of these pages ought to have seen many examples, perhaps the most fascinating being at St Thomas, Salisbury. Their purpose, of course, was to scare the bejaysus out of the population with graphic scenes of the horrors of damnation meted out to the sinners at the Dreadful Day of Judgement whilst the “saved” were marched off in self-satisfied columns by the angels to the sedate timelessness of Heaven*. The usual locations of such paintings - amongst the most entertaining art found in our churches - was above the chancel arch towards which the congregation’s eyes could hardly avoid being drawn. The ancient and rather oddly-shaped thirteenth century chancel archway here, however, would not have been an easy or very large canvas upon which to show these delights so at Oddington they decided to paint it on the north side of the nave instead. Its survival is something of a miracle. In the middle of the nineteenth century the church was more or less abandoned in favour of the new church of the Holy Ascension within the modern village. The wall painting had been whitewashed but was thus spared the maniacal zeal of the Victorians to strip the plaster back to the bare stonework. The restoration of 1912 revealed the paintwork underneath the whitewash. *Being a rather naughty boy, I am always amused by the words of Edmund Blackadder before he became England’s most ungodly Archbishop of Canterbury: “Heaven is for people who like the sorts of things that go in in heaven - singing, talking to God, watering pot plants. Whereas hell is for people who like other sorts of things...” |

|

|

|

Left: The view as you enter through the south door. The arcade is cut through the nave of the Norman church to reveal its thirteenth century replacement beyond; and that is adorned from end to end with the doom painting. Right: With apologies for a picture blighted by impossible light, this is the view to the east and the “new” chance.” |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. It is a very unusual triple lancet. All are of the same height and the heads are cusped. Note the nicely carved reredos, added in 1912 to the memory of the son of the incumbent who died at Ypres.. Right: This is the east end of what was originally the Norman nave and is now the south aisle. The window is Early English but the window space is surely Norman. As is the piscina to the right. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The west end of the south aisle and originally the west wall of the Norman nave. Again, you have to believe that the window rebate is Norman. Centre: Looking through the low archway into the south chapel. Here we have a problem. Why is this low round headed doorway set into a very large filled-in Gothic archway? If this was the original Norman chancel then you would expect the doorway to be of this round-headed profile - although somewhat larger. The only rational explanation is that the big arch replaced an original one but that it was then filled in and this simple one re-inserted. That explains what this archway is simply cut through the wall. As the chapel supports the tower above it, I rather suspect that it was to strengthen it. Jenkins, by the way, has surely got this wrong. He implies that the arch was filled in for strength when the church was expanded and the tower added. Sorry, Simon, but that makes no sense. That filled-in arch was not Norman. Right: The simple but very pretty Jacobean pulpit. still with its tester (the sounding board). |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: Where there might have been a doom painting we have instead a very unusual example of royal arms painted on the wall, in this case dated 1835, the reign of William IV. Right: This primitive stone bench has deep grooves that are attributed to the sharpening of arrowheads by archers. A beguiling thought! |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking down the “new” nave to the Perpendicular style west window. Right: The south porch with a couple of reticulated Decorated style windows of the fourteenth century. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The fifteenth century font. Centre: An ancient bench end. Right: The tower from the south. It is an unusual position but, of course, owes that to the way the church was remodelled in the thirteenth century. The lowest window seems to be a Decorated style replacement. The next two windows are Early English. The rectangular Perpendicular style bell opening dates from the addition of the belfry in the fifteenth century. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north east. The chancel still has its Early English lancet windows. You can just see a filled-in north doorway. The top of it has been glazed. The only other window in this wall is hidden behind the buttress at the west end of the chancel. You might have expected more windows to have been inserted when the nave was built. Were they filled in to facilitate a more continuous length of wall for the Doom painting a century later? Whatever the answer to that question I cannot help feeling that the Doom painting itself probably inhibited future generations from inserting more windows, satisfying themselves, it seems, with the west window of the fifteenth century. Right: The church from the south west, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west wall with the large fifteenth century window to the nave. What is now the south aisle to the right is what would have been the west wall of the whole church during the Norman period. It was, from this angle, a very tall nave and we need to remind ourselves that it was originally an Anglo-Saxon structure. The monument cut into the wall below the Early English window above is an ugly disfigurement, as are all such insertions. Right: A well-preserved mass dial. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

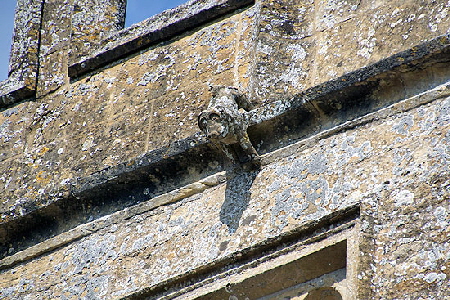

Left: Gloucestershire is not quite in the “hunky punk” territory of Somerset gargoyles but this dog on top of the belfry stage of the tower is certainly out of the same stable (or should that be kennel?). We can take things like this for example. Take a look at how his back legs are set into the wall above the parapet and his front legs into the cornice below. It is a clever and painstaking arrangement. Is he a gargoyle at all? I see no sign of a drainage hole but maybe I just can’t see it. Three Carvings Right: These are corbels on the north wall, supporting the fifteenth century roof. I am always intrigued by king carvings of this time. That on the left is Henry IV. I have said many times on these pages that he is easily recognisable by the fact he is bearded. His predecessor, Richard II had only a thin chin-line beard. And it is simple fact that from what we can see from contemporary portraits after Henry IV the next bearded monarch was Henry VIII in 1509! This might surprise you, as it did me. Henry IV’s beard was forked and you can see here that the sculptor has represented this by simply carving a cleft. The crown has three fleurs de lys, representing Henry’s futile claim to be King of France. You can see more about this symbolism in my description of the baptismal fonts at Harlaxton and Allington in Lincolnshire. Are the other two kings - with single fleurs de lys - also Henry IV? If not they must be Edward III and as his reign ended in 1377 that seems unlikely. It seems then that the fifteenth century roof here can be more precisely dated to 1399-1413. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Doom Painting |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Christ (top centre) presides over the Day of Judgement. Saints and Apostles flank him. You can just make out a trumpet being used by an angel to awaken the dead. To the left angels swarm around the righteous. On the right are the people who didn’t get on the Heavenly Train. Various demons and imps eagerly marshal them to their eternal suffering. A woman can clearly be seen hanging from a gallows. To her right fire a cauldron of sinners boils over flames, a winged demon taunting them. |

|

|

To the right of the window is the towering figure of Satan dressed in a fetching little number and surrounded by more of his demonic army. |

|

|

|

The faint-hearted might want to avert their eyes at this point as we see close ups of the horrors awaiting many of us. You have been warned |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||