|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“improvers” we might have had much more; but sadly they had a penchant for “scraping” all plaster from internal stonework, taking the concealed paintwork with it. Ironically, Hardham’s paintings began to be uncovered during the Victorian era in 1866. Various injudicious conservation treatments did much more harm than good, causing darkening and blistering. What the Church Guide calls “more sympathetic” treatment was carried out between 1961 and 1963 but nevertheless some detail was lost. Further work was carried out in the eighties and nineties using the best techniques available. Whatever has been lost, the survival of what remains is near-miraculous. Definitely a case of glass being rather more than half-full. Beneath the whitewash you can clearly discern the rough undressed stonework of the walls. There has been a minimal amount of refenestration so what you see today – with the exception of the Victorian porch bell tower - is pretty much what you would have seen a thousand years ago. It is a very exciting church indeed. To the south side of the chancel is a filled in squint that it is all that remains of an anchorite cell. Many such sites are somewhat speculative but it is known that in 1253 St Richard of Chichester bequeathed money to the anchorite of the time so its provenance seems unimpeachable. It should be noted, however, that anchoritism was vested in the individual, not in the building: that it to say that the death of an incumbent did not necessarily lead to the immuration of a successor. The status of anchorite was a serious matter requiring authorisation from a bishop and was taken anything but lightly as we know from the anchorhold at Shere in Surrey. |

|

Please note that the lighting in churches - large areas of low light interspersed with highlights created by windows - makes photography in churches challenging at the best of times. Unless you use sophisticated equipment - and I don’t have time or the inclination - flash replaces detail with a mass of yellow light. So I rarely use flash and it is utterly hopeless for wall paintings, as well as potentially damaging. In many cathedrals around the world flash photography is forbidden for this very reason. All of the pictures below are shot using “available light”. The ambient light changes within the church, however, and colours that are emphatic in one part are washed out in another and vice-versa. Detail can still disappear so I have to use Photoshop to make sure that most elements of the paintings are discernible here, sometimes at the cost of consistency in tone and colour. Inevitably what you see here is not quite what you would see with your own eyes - which is a very good reason to make your own visit! All notes on the content of the paintings are taken from the Church Guide. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

The impact that the church makes on first entering cannot be overstated. You are effectively entering an eleventh century art gallery It is hard to decide what to look at first. Left: Looking eastwards your eyes are of course drawn first to the chancel arch which is plain but, probably due to the absence of later subsidence-inducing “add ons”, still geometrically regular. If you ignore the woodwork and allow for the replacement of the original eleventh century east window with a later Gothic one, you are essentially seeing what a parishioner would have seen a thousand years ago. Right: Looking into the chancel we can see that the story continues. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

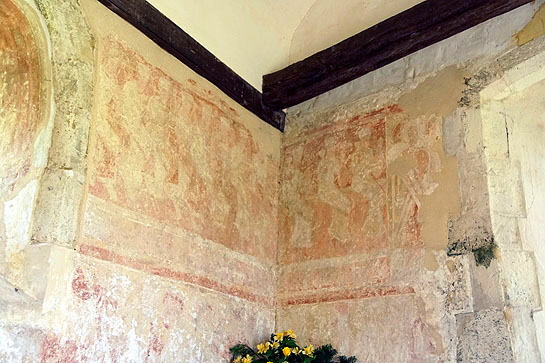

Left: Looking towards the west end. Note the original windows high on the left and right walls. Notice that the walls are effectively divided horizontally so that there are two courses of painting. Right: When you compare painting of this antiquity with that of, say, three hundred years later, the first thing worth noticing is that the area above and around the chancel arch was not reserved for a blood-curdling “doom” painting to cow the congregation into spiritual submission. So at Hardham we have the altogether more gentle and calming image of Christ flanked by two angels. Note that even the soffit of the arch has been painted with the illusion of alternately divided stones. Don’t think the congregation was let off though: Hell and all the rest of it was reserved for the west wall....! |

|

|

||||||||||

|

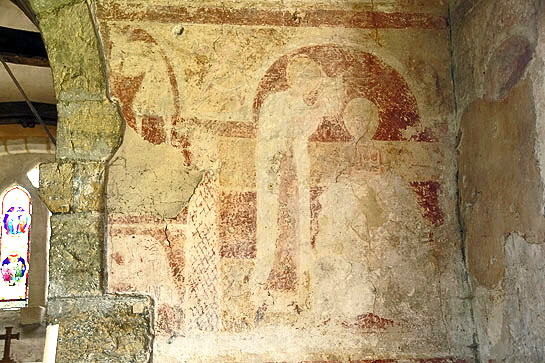

Left: To the north of the chancel arch, upper panel. Christ among Doctors (of the Temple) Right: To the south of the of the chancel wall upper panel we see the Annunciation (left) and the Visitation (right) with Mary and St Elizabeth embracing. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: North Wall. The Flight into Egypt. Joseph leads a donkey on which are mounted the Virgin and Child. Right: North Wall. Poor old St George bound to a spoked wheel. The whole north wall lower tier is about the life of old Georgie the Dragonslayer. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: St George in much happier times spearing some unfortunate “Saracen” at the Battle of Antioch . A naked victim lies under the horse’s hooves. Right: Still on the north wall, you can see how stylised decoration was used even into the splays of the original windows. To the left is the Massacre of the Innocents. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

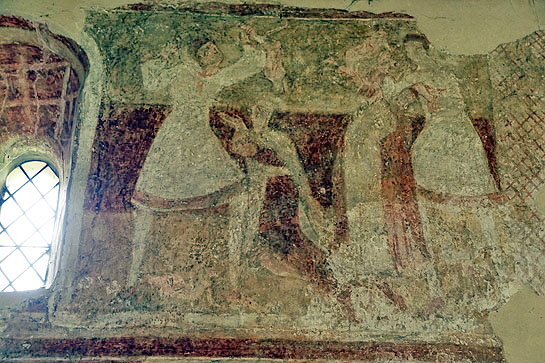

Left: The Massacre of the Innocents, North wall. Two soldiers (left and right) are at their grisly work. The soldier on the left is holding a child by the ankle while its mother begs for mercy. Right: Whilst on the subject of grisly, this is St George being held by two torturers (you rather wonder why the church was not dedicated to him?) |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: On the north wall of the chancel, just beyond the arch are these two apostolic group shots. The upper group shows just six apostles. The ether six are on the south side. Below the six here is a Last Supper scene. It is said by some that Leonardo da Vinci copied it after popping in during a holiday to Bognor Regis. I’m sceptical. I heard it was Brighton. Right: On the north wall in the western corner is the Adoration of the Magi. You can just make out the three wise men. |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: A peculiar extension to the Flight into Egypt scene. As the Holy Family arrive at the town of Sotina the pagan idols fall. Centre: My favourite panel seen on the reverse side of the chancel arch. This is Adam and Eve, of course. No church should be without them. Explain this to me, though. I know why mediaeval painters and sculptors struggled with, say, elephants and lions that they’d never seen. I know that they had no idea of the body’s internal mechanisms. I suppose mirrors were a rarity. But can someone tell me why they struggled so much to depict even a passing resemblance to the human body? I know it was all wrong for Adam and Eve to have fancied each other - I blame the serpent - and that even subsequently procreation should preferably have been carried our without pleasure and for the sole purpose of creating new sinners. But had these blokes never seen a naked human body before? I’m surprised the two of them could summon the necessary enthusiasm - even if they had been supplied with the necessary body parts. Anyway this scene represents the temptation with the head of the serpent visible by Eve’s outstretched hand. Right: The serpent is a particularly elaborate one and has wings which is a bit novel and he doesn’t look as villainous as most such serpents. The Church Guide points out that these scenes are in the unusual style of a wall hanging. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: On the west side of the arch we can see Adam and Eve sitting back to back in the lower pane, trying to conceal their nakedness. Above that is a very unusual scene indeed of Eve milking a rather unusually-shaped cow which! Adam is amongst branches upper left. These are the Labours of Adam and Eve although Adam seems to be leaving most of it to his illicit missus. Centre: This looks quite a different style to many other of the paintings. The faces look almost classical to my untutored eye. Adam and Eve, now “fallen” and feeling pretty sorry for themselves. They are apparently hiding their lower halves in a bath of water although Eve has apparently not yet worked out that showing her breasts will also frowned upon somewhat. You can see here some of the surviving blue paint. Right: The window splays were painted with stylised decoration. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: Turning round the corner from the south to the east walls of the chancel are the twenty four Elders of the Apocalypse. Right: Looking now at the south wall of the nave, we can see at the left hand side a part of a nativity scene. Christ lies swaddled - almost mummified! - in his manger with animals around him. The rest of the nativity scene is discernible but quite damaged so I haven’t shown it here. To the right of the nativity is a scene from the Labours of the Month, although it’s impossible to detect which it is. A labourer can be seen on the right shouldering an agricultural implement of some kind. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: On the south east wall of the chancel arch lower tier. To the upper right of the chancel arch is the Annunciation and below it is the Annunciation to the Shepherds. Frankly, these are almost indistinguishable even on “blown up” pictures. To the right, though, is the altogether more visible image of the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist who is holding a book over Christ’s head. The Church Guide avers that this is a rare image that derives from early Christian art with the “book” being a scroll representing St John’s sermon on repentance. I thought I had never seen this imagery before but the Church Guide helpfully reveals that the only other English example is on the Norman font at West Haddon in Northamptonshire which you can see on this website. Right: The west wall of the nave has the usual Hell scenes, albeit in an unaccustomed place. I’m afraid I can’t make out what is happening to these chaps but I’m sure it’s too good for them... |

|

It would be pointless to try to reproduce all of the images here. There are thirty-nine “panels” in all and some are very difficult to make out through photography. Do make your own visit because the overall scheme and its near-completeness are as important, perhaps more so, than the individual paintings. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The south side of the church. Note the large blocked up doorway that seems to have been topped by a lintel rather than an arch. Right: This is the only remaining original window on the south side. When one considers the lack of natural light that would have been entering the original church it is interesting to speculate what would have been the effect of the congregation seeing all of the elaborate paintwork lit mainly by guttering (and smelly) candles. In what other context would these people have seen art at all? They must have been awe-struck. |

|

|

|||

|

Left: The quoin between nave and chancel, It is formed of fairly conventional stone blocks rather than the classic “long and short work” of earlier Anglo-Saxon work. The lancet window is probably early fourteenth century. Right: The east end. The style is very early Early English with the “tracery” being just a hole knocked through the stone. |

||||

|

|

||||