|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

respectively. The clerestory is fifteenth century. The aisles clasp the chancel on either side. With its ironstone and relative symmetry the church presents a very pretty face to the world but, that west door apart, it is the contents of the church rather than its shell that sets the pulse racing. Misericords, superb monuments, mediaeval glass - there is plenty here for the church crawler. Let’s take a look. |

|

|

|

|

Left: The Anglo-Saxon style (hedging my bets here) west doorway. It is not just the shape that screams “pre-Conquest” it is the massive stones that frame it. Yet not only Pevsner but also Taylor & Taylor’s epic “Anglo-Saxon Architecture” ignores it. As they do not even include it in their (I paraphrase) “those we have discounted” chapter I have to conclude they simply missed it. Perhaps they believed that it is an anachronistic inclusion in an otherwise Norman tower (as Pevsner seems to) but I am still a bit dumbfounded. Note the mismatch of door sill and ground level. How come? Above the doorway is a lancet window that is clearly a clumsy later insertion from the early thirteenth century. Doorway and window are two styles apart! Work it out for yourself. Centre: Looking towards the west wall. The old roofline is clearly visible. The tower doorway looks Early English. But what was here before? Right: Looking east into the chancel. The attractive Decorated east window is of 1883. A print of 1830 shows a very utilitarian rectangular window of three lights. |

|

|

|

|

Left: The font. With its commonplace blind arcading decoration and its cable moulding around its rim, it is a classic Norman design. The Church Guide, however, points to the cusping within each arch and suggest that it is likely, therefore, to be an early thirteenth century font with a late Norman flavour. Centre: An attractive piscina in the north aisle. It is, however, not original and the Church Guide speculates that it was made to match Philip de Gayton’s tomb when the north chapel was restored. Right: One of the real treasures of this church - the Tudor alabaster tomb of Francis Tanfield (1508-1558). He wanted his body “to be buried not sumptuously but seemly for my degree (ie his class) in my chapel chancel”. The alabaster table top is both fascinating and touching, Amongst other things, it amply demonstrates the fecundity of such families and the dreadful rate of infant mortality. Francis and his long-suffering wife, Bridget, produced eighteen children of whom eight died in infancy. Bridget outlived her husband by twenty-five years, reaching the ripe old age (at the time) of seventy. Just think about the implications of this. If Bridget had her first child at the age of fourteen and was unable to conceive beyond the age of (say) thirty eight - both liberal estimates - she bore a child every eighteen months of her childbearing life and buried one every three years. To have survived eighteen pregnancies and lived until she was seventy in Tudor England was surely astonishing? |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The perils of infancy are laid bare here with deceased children depicted in their shrouds. One poor soul has been added as an afterthought. Right: The heads have suffered through the centuries. Despite not having been knighted, Francis cuts a martial figure. His wife is presumably depicted here as she was a quarter of a century before her own death. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two more monuments of great rarity. Left: the wooden effigy of Philip de Gayton (d.1316). Such survivals are exceedingly rare and, moreover many of those that have survived have been ravaged by weathering and by woodworm! He was not a crusader, but his armour is a wonderful source for those who love military costume. Right: A rare stone memorial to a child. It was found being used as a building block in the east wall of the north chapel. It is Mabila, daughter of Thomas de Murdak and Juliane, daughter of Philip de Gayton. The de Murdak name has been partly erased from Mabila’s monument. This is because Juliane murdered her husband at the instigation of one Sir John Vaux in 1316 - the year of Philip’s death - for which crime she was burnt at the stake. What a remarkable story! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

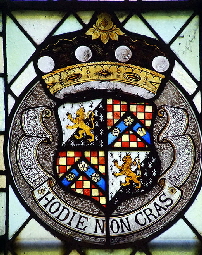

Left: The effigy of Scholastica, wife of Philip de Gayton (effigy above). The Church Guide says this effigy pre-dates his wooden one, which is remarkable. “Scholastica” - there’s a hostage to fortune as a name! This is a quite interesting figure. Her dress is naturally draped, her arms in a naturalistic pose. This looks like a real person. Compare it with the stiff formality of the depiction of Bridget Tanfield three centuries later. I wonder if it is because, having pre-deceased Philip, her effigy did not have to complement or enhance that of her husband? Centre: Although thirteenth century tomb covers are not exactly rare, this one is particularly finely decorated. Right: This is the only surviving mediaeval glass here - the coat of arms of Philip de Gayton. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The east end of the north aisle. On the left is the Tanfield tomb. To the right, open to both aisle and chancel, is the wooden effigy of Sir Philip Gayton. You can also just make out the Mabila memorial stone set in the left wall within the recess of the tomb of Scholastica de Gayton. Right: The north aisle looking towards the west. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking into the chancel. The two misericord ranges can be seen left and right foreground. The east window in Decorated style is Victorian. Right: A piscina with a tell-tale course of nail head carving announcing its Early English provenance. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now for the bonkers feature of this church. The chapel window has a great array of Flemish painted roundels. They are not very common. The madness, though, is that they are from Beauvais Church in France! I am indebted to the excellent Church Guide as to how they came to be here. Rev George Butler was rector here 1814-53 and was responsible for restoration work in 1827-8. George was looking for some glass to enhance his church. He had been headmaster of Harrow School and one of his pupils was William Henry Fox-Talbot, lord of the manor at Laycock Abbey. If that name sounds vaguely familiar, it is because he was one of the most important pioneers of photography. Fox Talbot’s uncle bought a box of glass from Beauvais, intending to use it for his own country house. It wasn’t right for his purposes so he gave it to Fox Talbot who in turn gave it to Butler. It was put into the east window and then moved to the chapel when a new chancel was built. So in these four pictures we have four pieces of French heraldry gracing a church in rural Northants. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four more of the Flemish roundels. Note the two very interesting fashion designs in some of these. The picture right is dated 1632. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And so to the misericords! These are of very fine quality indeed. There are only six and it is tormenting to think that there were perhaps many more that were simply disposed of. Four are of religious scenes which is quite unusual for misericords which counter-intuitively more often had quite worldly, even subversive, designs. The supporters, however, (that is, the designs either side of the main one) are more flamboyant. This misericord is a cautionary tale. A figure clothed in feathers and with cloven hooves sits astride a couple, their rosary cast aside. GL Remnant whose “Catalogue of Misericords in Great Britain” (Oxford, 1969) is regarded as definitive suggests the Devil is eavesdropping on their conversation. In fact it is more specifically Tutivillus whose special job this was in Satan’s world. The two people are in church, hence the rosary. The left supporter is an ape, an instrument of the Devil. On the right a sphinx-like person waits to write down their words. The evidence will go against the couple on the Day of Judgement. See another example at Enville in Staffordshire (and after you have looked at that be sure to return to see my “World’s Greatest Church Trail”, of which it is part!) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another very mediaeval scene. Remnant describes this as a lion and and a dragon locked in combat over the body of a smaller animal - I would suggest a pig, looking at the ears. The Church Guide suggests it is a lion cub “representing the next generation”. The supporters are almost as much fun as the vignette. On the left a winged creature is grasping a fish. Another dragon - perhaps the offspring of the central one - seems to be preening his tail scales! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the two misericords pronounced “national treasures” in the Church Guide for their rarity. An image of the Three Marys. An angel above their heads announces Christ’s resurrection. The supporters are very brash compositions of crowns, oak leaves and acorns. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Virgin Mary in long flowing gown and rather anachronistic-looking headwear embracing four naked figures. These are probably souls being protected on the Day of Judgement. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Last Judgement with six rather anxious-looking souls clustered around Christ who has been defaced |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another special scene. Christ enters Jerusalem seated on an ass. The iconoclasts have decapitated him. The supporters are particularly beautiful. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These misericords would not have started life here. They would have been in an abbey or collegiate church that required the monks or canons to recite eight masses a day and would have become redundant when those institutions were dissolved. The Church Guide believes that they came from St James Abbey in Northampton. The Rector of Gayton at that time was a Gifford and it was the Gifford family who bought the dissolved abbey. So far, so good. But that does not look to be the whole story here. Remnant was of the view, without explaining why, that the two “traditional” images (call them Group A) - the dragon and lion and the Tutivillus scene - were fourteenth century and the others (call them Group B) fifteenth century. He goes further and quotes one Arthur Gardner - an author of the 1950s - that the central figures in Group B might even be “foreign” work since the subject matter is so unusual in England. Moreover, Gardner suggested that the central designs in Group B had been reset into later seats and that the supporters also date from the resetting. Looking at the last statement first, it seems to me to be true. Whereas the Group A misericords have central designs that simply blend into the seat, those of Group B all seem to sit on little triangular plinths of wood that looks newer than the central designs. Similarly, the supporters look fresher. We could also add that these supporters are larger than any mediaeval ones I have seen. I believe Gardner was right. Quite how a misericord design is detached from its original setting, however, I do not know. As for Group B being “foreign work” that must be speculation and the argument that the designs are unusual for England is not altogether convincing. Unusual, yes, but hardly sensational! These misericords would almost certainly have come from a much larger range the rest of which are lost to us and it could be that these four misericords that form Group B were the ones that the Rector thought worthy of retention precisely because they were rare religious scenes. Would a mediaeval English abbey import a whole lot of misericords from Europe and, if so, why? And when, one wonders, did the defacements occur? If they were thought worthy of saving, we must presume that it had happened after they were relocated, possibly during the Commonwealth period? As for their being a century apart in age, again I am not wholly convinced. Look at the eyes on the Tutivillus design and then look at those on the group B carvings. They look the same to me. Perhaps Gardner (and Remnant) have read too much into the rarity of the religious misericord iconography? I do not really have any answers. We must simply enjoy a set of six of the best misericords you are likely to see! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The southern range of three misericords, all from “Group B”. Right: Armrest carving from the misericord ranges. Some of these also seem to have been restored asking more questions of how these misericords arrived here and when. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south porch is of uncertain date but no later than the seventeenth century. The doorway within is fourteenth century but both porch and doorway were moved to this position - using the original masonry - in 1827. Centre: A north door. The Church Guide quite rightly points out that for any church to have three north doors as this one does is extraordinary. Right: A real peculiarity here. This doorway, hidden behind a buttress on the north side was the private entrance for the manorial lord into the chapel. at a time when it was not accessible from the rest of the church. It is odd enough. More odd still is that this area is also the termination of a secret passage from the manor to the church. This is not one of those apocryphal “secret passages” of which there are so many but a real one that collapsed in 1815 when a road was constructed over it. The reason it as here was almost certainly to facilitate the passage of Roman Catholic priests to the church to conduct illegal private masses during the Elizabethan period. A similar documented passage is known at Southrop in Gloucestershire. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two nice carved label stops. That on the right looks like the Vatican. I have been unable to trace the origins of that on the left. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Those who have read my “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers” polemic will know my preoccupation with East Midlands cornice friezes. Tower friezes can be a bit half-hearted and often suffer from serious weathering as their positions are so exposed. This one is not overly flamboyant but it is very well carved and has survived in terrific condition, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The church from the south west. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And finally! I think that this church, photographed on a sunny Spring morning, with its ironstone glowing, is just gorgeous. Even that peculiar chimney is somehow charming rather than grim. England at its glorious, enchanting best. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||