|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

English triple lancet but the latter is a nineteenth century replacement look at the unplastered west side of the chancel arch immediately reveals the outline of a Norman or even Anglo-Saxon round headed arch. Its height - above the broad Gothic arch which replaced it - suggests to me a window rather than an arch but most commentators seem to feel it was the latter. Taylor & Taylor calculated it would have been thirteen feet high by five feet wide. The chancel itself is almost certainly pre-Conquest originally. But it has been altered and extended over the centuries. As with many churches as simple and ancient as this one, the distinction between pre- and post-Conquest can be hard to make and we have to be content with the knowledge that it is certainly eleventh century and not later. Either way, it pre-dates the Norman aisle which dates from around 1175. Dating is always a problem here. How old is that chancel arch? I have seen speculation of both fourteenth and fifteenth centuries but such is the unfashionable nature of this church, indeed perhaps of this area, that we cannot be absolutely sure. The aisle itself is gabled, almost a separate structure. It is extremely narrow. At the west end we see a lancet window and a filled-in round window above it, both surrounded by crude zig-zag moulding. The undersides of the window rebates on the north side also have zig-zag but these date from an 1866 remodelling as the well-mannered sandstone jamb stones attest. The bell tower at the south west corner is a curious thing and appears to be thirteenth century. If you are looking for elegant high gothic architecture this place will leave you cold. If your boat is floated by a humble church in an ancient and spiritual location, then this one is for you. As it very definitely is for me! |

|

|

|

Left: Looking towards the hard-to-date chancel arch. The Norman north aisle is to the left. You might see pictures that show a much brighter church than this but, believe me, even mine somewhat enhance the actual light here. There is no sign that there was ever a screen here. Right: The chancel . The east window is Victorian. That this room is of pre-Conquest origin is almost beyond debate but how far that original chancel extended is perhaps not quite so settled. Note the priest’s door to the right with its round arch comprising just two pieces of stone. |

|

|

||||||

|

Left: Looking through the chancel arch to the west wall beyond. Above the arch you can see the outline of a pre-Conquest arch. Such an arch would be very high and narrow. There are a few such lofty pre-Conquest chancel arches in the country. Is this one? Note that the arch is not central. Externally the chancel is symmetrical either side of a gabled roof so the we can see that the chancel was extended northwards. The large squint to the the right here suggests that this extension was contemporary with the the building of the north aisle in about 1175. Note the ladder to the bell tower. Right: The north arcade with its uncompromising capitals. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The western capital with its rustic- to say the least - carvings. A muzzled bear - a favourite mediaeval motif is to the left, a girning man to the right. Right: A capital with stylised carving and some damage. |

|

|

||||||||||

|

It is quite hard to see what the man and the bear are supposed to be doing. They look like they are peering over some kind of barrier - a plant stem. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: A damaged face peers out from the eastern capital. Right: Another odd one. Is it stylised or is that a big fat tongue emanating from a mouth? |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Left: The priest’s door in the south wall of the chancel. The head is of a rather strange profile - a slightly depressed round head. The lintel is made from just two pieces of stone. Centre: If the priest’s door looks pre-Conquest this piscina seems even more so. The head is made of a single piece of stone. This is masonry at its most crude and, in truth, it is hard to think the work had anything to do with “styles”. This was surely about making use of the stone that was around in the most basic way by men with the minimum of skills. Right: The hefty squint through the north aisle to the chancel. Was it there so the congregation could see the host raised? Was there a little altar here and the squint was there to ensure the hosts were raised simultaneously? This is often a matter of debate but in this simple church it seems much more likely that it was for the benefit of the congregation. |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: Pevsner has the odd little tower as likely to be of the thirteenth century. It seems to have been repaired. Pevsner may have been right but the arch heads look a little sophisticated for that time. Certainly the little parapet with tiny pinnacles and simple rosette decorations looks considerably later than the rest. It is really quite endearing. Centre: The south doorway has the same odd flattened round head as the priest’s door. The head and the jambs do not seem to be of the same date. Is it contemporary with the arcade perhaps? Right: The priest’s door from the outside has the same idiosyncratic construction. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

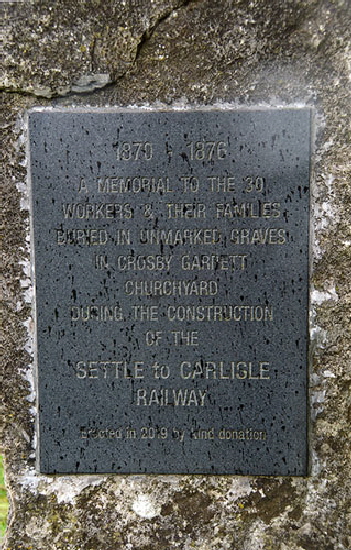

Left: The west window of the aisle. Above it a filled-in round window. These windows are surely original Norman. Centre: In the churchyard is a touching memorial to the nameless people who perished in the building of the Settle & Carlisle Railway that is a major tourist attraction to this day. The railway crosses the Crosby Garrett viaduct very close to the church. How very sad that it was not thought worthwhile to record their names. Right Upper: The round window of the north aisle. Right Lower: One of the beams in the porch records its date. Four years before the Great Plague of 1666 when the useless Charles II was on the throne. |

|

|

|

Left: The church from the south west. The north windows are Victorian replacements. Right: The view of the church from the village below. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

That rebuilding bequeathed us two Norman capitals, one of which is certainly worth comparing with its counterparts up the road at Crosby. But the most important thing here is the “Loki Stone” or “Devil’s Stone. Loki was a Scandinavian god, described thus by Philip Parker in his “The Northman’s Fury” (Jonathan Cape, 2014) : “...a highly ambivalent character, who is the product of the union of a goddess and a giant. A mischievous trickster, he seems constantly at odds with the Aesir (the main gods of the Scandinavian pantheon), and his actions often seem to align him more with the god’s adversaries - the dwarves, giants and various monsters of the lower worlds - than on the side of Odin, Thor or Freyja” . It seems that northern Christians seized on Loki’s duplicitous nature to personify the notion of the devil in disguise. The stone here is one of only two thus in the whole of Europe. Also here is a fine cross head and parts of cross shafts. Of great importance, too, is a hogback - the most mysterious of Norse (again, not Danish) survivals, that remarkably are found in the UK but not elsewhere in Europe or Scandinavia. For much more about these see Heysham in Lancashire. This is an easy church to visit, right in the heart of this small but bustling community that attracts many visitors en route to the Lake District or walkers on the legendary Coast to Coast Path. It is an attractive church to visit. But do try to visit Crosby as well. Together these two churches represent a Norse enclave in what an area which has a particularly hazy first millennium history, |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Pre-Conquest survivors. Left: The Loki Stone. Curiously, he has hls hands bound. The most likely explanation seems to be that in one legend he was bound to a stone by fellow gods (he was an annoying little bugger) and tormented by fiery venom from a serpent. Another curiosity is that his devil’s horns are pointing downwards. AD900-1000 is the most likely dating. Right Upper: A beautiful surviving cross head. Right Lower: The hogback is a simple one but they are all precious and almost exclusively seen in the norht west - see Heysham. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: A surviving capital from the Norman church. A strange image of two beasts sharing a head. Compare it with the capitals at Crosby Garrett, They are very close in age. Did the same man carve them all? Right: A very different capital with stylised leaf decoration (note: I have inverted this picture). The two capitals do not look lime contemporaries. |

|

||

|

It would be remiss of me not to include a picture of Kirkby Stephen’s magnificent Early English style nave with its seven bays. I am afraid that most of the chancel and the nave were remodelled in Victorian times, including this nave but it is still a thing of great splendour. My goodness, how the fates of these two churches have diverged since 1170! |

||