|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south. This is actually the south aisle which has a gabled profile, reflecting its rebuilding. Right: Looking to the west. The north arcade is original late Norman. Note the relatively narrow columns and the plain and somewhat clumsy-looking capitals. The south aisle was also Norman but it was widened in about 1340. You can just make out the Decorated style tracery of its east window. The arcade rebuilt in 1868 leading to a slightly unfortunate lack of symmetry in the church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west. Right: The chancel is pure Decorated style, dating from 1330-40. The east window was restored. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking from the chancel arch into the Norman north aisle. Because it is unchanged since it was built - with the exception of the Gothic-style windows - it still has its original lean-to roofline. Right: The rather odd north arcade capitals with distinctly unambitious decoration. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And so to the font which is by any standards, a stunner. It is ambitious, well-executed and full of symbolism, much of which is a lost on us today. There are four bands of decorative work enclosing a series of eight graphic designs contained within roundels. The roundels are separated by masks. Left: One of the roundels contains an Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) which is the most recognisable motif in the whole Norman canon. To its right is an unidentifiable animal with a conspicuously long tail with a luxuriant end! Right: As we progress anti-clockwise around the bowl we see two geometric designs. The one in the centre is of this shot is the one that Marty Curtis Webb illustrated in her book - more about that in a later picture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The second of the geometric designs has four intertwined circles with a hub at the centre. We can’t know what this means. Is it meaningless? Possibly not, since it sits next to one the designs that Mary Webb managed to decode. To its right a bird tries to peck at a smaller one. Right: Here a griffin turns to peck his neck. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The pecking bird is on the left. To the right is a petal design. In between the usual mask has been replaced by a stylised figure holding foliage in each hand. Right: The geometric shape that interested Mary Webb. She didn’t have a photograph but sketched it as one eight examples of interlaced squares. Photographs of other examples can be seen on this site at Sculthorpe, at St Peter’s Northampton, and most importantly on the font at Stone in Bucks where her quest began. To cut a very long story short, Plato regarded a double square (or a figure eight) as being a representation of a cube - his “elemental solid”. This is pretty esoteric stuff and for the connoisseur or anorak (yes, I have my hand up!). You need to read the book to discover how compelling Mary Webb’s arguments are. This is not quite the only font of the Herefordshire School with a Mary Webb interest. Rock in Worcestershire has a font with a circle interlaced with arcs. Malcolm Thurlby does not refer to the Mary Webb angle in his book about the Herefordshire School although I am sure he has read her work. That the Herefordshire School masons should carve such imagery is no surprise at all. Although their patrons were laymen their origins and many of their influences were gained in service to Hereford Cathedral, a centre of mediaeval learning. How much influence monastic learning had on sculptural designs is always an open question. I am generally at the more sceptical end of the spectrum but certainly I believe that only monasteries would have had knowledge of neo-Platonist thinking. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four more close-ups of roundels that also amply demonstrate the problems of taking photographs from four different cardinal points in a church using available light rather than flash that washed out all the detail! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

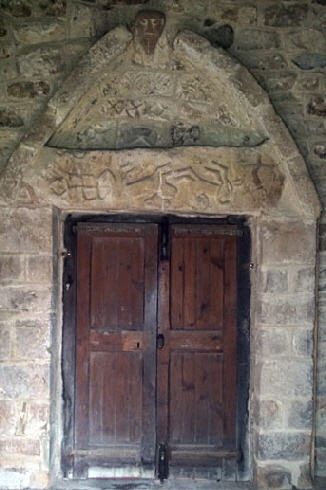

Left: The base of the tower from the south west. If you look closely you can make out courses of masonry that hint at previous window spaces but this is not remarked upon elsewhere so maybe I am deluding myself. Note the west lancet window of the aisle. Right: The gable to the porch presents us with a carving that surely was part of the original Norman church although from what part is anybody’s guess. Interestingly the Church Guide claims that the porch was moved to its present position in 1340 and that its doorway has its original Norman arch. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Anglo-Saxon west door is hidden inside the tower. Because the west end is dominated by the church organ it is easy to miss it and you need to dodge around some a bit of clutter to get there. Right: The area above the doorway is really in two parts: a massive stone lintel.with figure sculpture and an area of crude geometric carvings forming a tympanum. The whole is surrounded by an untidy hood mould (bear in mind, this was originally the external west door to the church) and is topped by a carving of a human face. Taylor & Taylor in their epic “Anglo-Saxon Architecture” (OUP 1965) suggest that the lintel is in itself the base of an original tympanum but they are unable to speculate whether this tympanum was pointed or semi-circular in profile because the area above the lintel has “clearly been much disturbed. We cannot rely on the shape of the hood mould. Pevsner was of the view that the recessed area is Norman and so is the carved face above it. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is the door lintel turned upside down so you can see its design better. When I say I have turned it upside down, I do mean the photograph of course....To the left is a cat-like figure. There are two fairly obvious figures. The one on the left could be a cat or a dog. To the right of that is another animal figure. The Church Guide says it is a deer. That depends, I presume, on the indistinct area above the head being antlers. I can’t quite see it myself. To the right is a chequered pattern that the Church Guide is a portion of netting: they believe the whole thing to be a representation of a hunt. I have converted the picture to black and white because I think it makes the detail more discernible. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is the lintel the right way up. On the right hand side you can see if you look very carefully what seems to be an image of a cat. The head adjoins the very edge and it appears to be a quite definitely feline. All of this is pretty speculative, in my view, especially if Taylor & Taylor were right in their surmise that the lintel is only part of an original larger tympanum. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Just so that we call understand that digital photography is not perhaps the be-all and end-all the two pictures above were taken by renowned artist John Piper sometime between the 1930s and the 1980s. The photographs are in the custody of the Tate Gallery. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||