|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

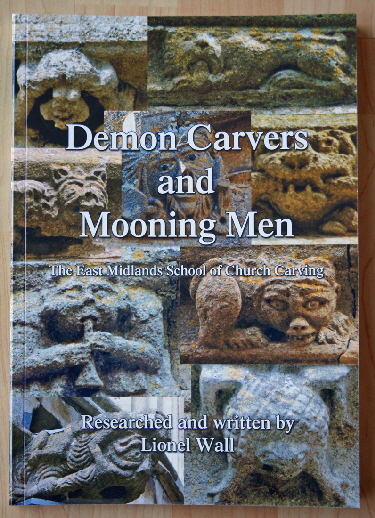

A few years ago I did what some correspondents had suggested and wrote a book. It’s not, though, about churches in general. Others have done that and I’m not really a “me too” kind of person - as I hope you might have noticed. My book - “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men” is about what I believe to be a “school” of external church carving within my part of the East Midlands. The research is original and focuses on a group of twenty or so churches where I believe an itinerant guild of stonemasons left some indelible marks of their presence, the main one being the inimitable and very rude “mooning man” image. The subject matter is very local encompassing an area stretching, very roughly, from Stamford in the east to the outskirts of Leicester in the west. For this reason nobody wanted to publish it which is a pity but very understandable. So I had it printed privately. Like the publishers you might well be thinking that it is no relevance outside the immediate area but I would beg to disagree. Many writers have touched upon the subject of the mediaeval stonemason but in truth there is hardly any evidence whatsoever about those anonymous humble men who built our ten thousand parish churches, as opposed to the grand men who constructed our cathedrals and abbeys. In my book you will become acquainted with “Ralf of Ryhall”, “The Gargoyle Master”, “Simon Cottesmore” and some others as they worked in this area in the early fifteenth century. They won’t have been very different from the men who carved at a church near you. The book is sold out in all versions and I am working on a possible second edition (as at 2020). The new edition will reflect a few more sites I have uncovered since the book was printed and will also give much more insight into the way the stonemasons worked. In the meantime if you want to read the first edition (115 pages when printed) - it is still mainly perfectly valid - I have made it available in .pdf format that I can email to you. The price for that is £4, payable via PayPal. Please email me at brumman47@hotmail.com if you would like this. All money received goes to the Churches Conservation Trust. The main churches covered are: Rutland: Ryhall, Oakham, Cottesmore, Whissendine, Langham, Market Overton, Empingham Leicestershire: Tilton-on-the-Hill, Lowesby, Wymondham, Knossington, Hungarton, Cold Overton, Buckminster, Owston, Beeby, Muston, Bottesford, Lincolnshire: Thurlby, Colsterworth, Careby, Irnham, Brant Broughton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Demon Carvers and Mooning Men - a Brief Precis |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Demon Carvers Over the years I have often thought about the men who built our churches and carved the images that so lavishly decorated them. What manner of men were these? How did they live? Did they work on more than one church? We know that the answer to that last question is “yes”. The problem is, though, that our parish churches have been changed often out of recognition over the centuries. Even if they had not been so changed, how are we to say with any certainty that Fred the Mason built the north aisle at one church and the tower in the church in the next village? Occasionally there will be an excited comments in a Church Guide that a mason’s mark in one church can be seen in another, but it’s hard to get too excited and it tell us nothing apart from the bleedin’ obvious that a mason might work at more than one church! A mason’s mark, by the way, was the unique mark that a mason would make on a block of stone to show it was his. This was useful for both payment and quality control purposes. At some of the great churches and cathedrals the names of master masons might be known, because proper records were kept. Sometimes with such magnificence it is possible to discern similarities in design but our parish church masons are as unknown to us as are the bricklayers that build houses for Wimpey and Barratts! There are, nevertheless one or two well-known “schools” of architecture. The Herefordshire and Worcestershire School is perhaps the best known. Active in the Norman period there are commonalities of design evident in tympani, doorways and baptismal fonts. It is quite an extensive estate both geographically and numerically. Tracing individual masons is more challenging but in some cases it has been possible to make an educated guess at who commissioned the work. You can see several examples on this website: Eardisley, Chaddesley Corbett, Rock and Kilpeck amongst them. The Northern Oxfordshire School of carving is also quite well-known. There the school is defined by the cornice friezes below church roofs and by distinctive designs on arcade capitals. See Adderbury, Bloxham and Hanwell. You might already have realised that what these “schools” have in common is that they are defined by their decoration and not by their masonry. We must assume that the same men also worked on the structures but it is hard to discern any surviving evidence. The East Midlands School is also evidenced by its cornice friezes. What makes it more significant than the Oxfordshire School, in my view, is that it covers more churches and that it allows us to identify the distinctive work of no fewer than five masons. We don’t just know there was a group or that they just influenced each other, we can put fictitious names to them and work out who was working with whom and where. Moreover, we can date all of their work to around the early fifteenth century. Because the nexus of work is so extensive it positively invites us to use the evidence to postulate some hypotheses as to why they did what they did and how they organised themselves. There are huge pitfalls here. It is tempting to see everything in the light of modern experience and industry. In my view the writers on mediaeval masonry have fallen into the opposite trap. They imbue the mediaeval man as living in a kind of holy terror, spending their lives in fear of divine retribution and with deep love of God and his works. Their world, we are led to believe, was of god-fearing austerity, the priest was their stern disciplinarian and joy and humour was forbidden. Through this model some well-intentioned writers search for hidden meaning in the most banal of church decoration. Thus, for example, that most pagan of images the “Green Man” must have some subliminal Christian message because paganism must be either non-existent or illicit. The most facetious of gargoyles must be there to ward off the Devil. In short, many commentators see mediaeval man as almost another species with none of the motivations, prejudices and doubts that we take for granted today. Tosh! In this account, therefore, I will not be fitting what I see to a set of pre-formed views of the mediaeval mason: I will be using what I see to inform us of the nature of the mediaeval mason, something about which precious little is known. Turn to a page about mediaeval masons in the average church history book and you will immediately be taken into the world of soaring Gothic cathedrals and extracts from the account books of abbeys and priories. This is not the world we are talking of here. This is the world of the common mason with many of the same blue collar attitudes and motivations as the blokes that build stuff today. Much of what have to say is prosaic. You might even say “so what?”. But, believe me, the prosaic has attracted far too little attention! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First Stirrings - Ryhall and Oakham This story begins at St John the Evangelist Church in Ryhall. I happen to live next door to it! I was keen to find something about it that would justify a page on my website, but I wasn’t optimistic. Ryhall’s is a fine church but none of the church architecture books give it the time of day. As it turned out, it has a stunning frieze of carvings around the parapets of its aisles and chancel. Everyone will have their favourite church carvings. Gargoyles, in particular, are popular with even the casual church visitor and several books have been written about them. You can even buy cast “gargoyles“ at your local Garden Centre! Ryhall, however, has a frieze with more than a hundred carvings around the roofs of its aisles and chancel. Friezes are not common. In the case of Ryhall’s frieze we see a tapestry of humour, cheek and scenes from everyday life. One group of the Ryhall carvings particularly caught my eye. They surround the south aisle. They are of fantastic creatures. They may be lions, they may be dogs. Take you choice. Their defining characteristics, however, are black stones for eyes, exaggerated manes or fur and mischievous grins. There are also quite exaggerated talons and claws. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A visit to Oakham Church a few months later revealed similar carvings around the north aisle. They were quite unmistakable and are surely by the same individual. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are the same black eyes, the same exaggerated claws and wavy manes. On the left hand carving you can even see a smaller figure to the left if the main one. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mooning Men , Hats and Fleas Seeing the link between Ryhall and Oakham not surprisingly led me to believe that the same carver might be seen elsewhere and I visited every church in the area where Pevsner had mentioned the magic word “Frieze”. At first I was convinced the same man had carved them all but as the number of churches grew and different styles emerged I realised I had been deluding myself. One of the reasons the delusion occurred in the first place was the frequency of two images. One was the “mooning man” where a man - his anatomy leaves his gender in no doubt! - bends over, puts his head between his legs and sticks his butt in the air. I found seventeen of these in all! Yes, you read that correctly - seventeen. So what, if you will forgive me labouring the point, was the religious significance of these!? Quite. There can be none. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mooners at Oakham (two left hand images), Lowesby and Whissendine |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So if they were not all done by one man why do we so many? It’s obvious, isn’t it? This was a bunch of men who knew each other leaving their collective “trademark”. It wasn’t a local tradition in the way that some areas of the country have characteristic architecture. Mooning men, in fact, appear throughout England and France although never as far as I can ascertain in the form they appear in the East Midlands and usually even then as gargoyles and definitely not as frieze carvings. A vital piece of information lies in the form of the ubiquitous image of a woman wearing a square headdress. Every church in this group has them - often several. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Square Headdresses at Langham, Ryhall, Lowesby and Oakham |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Head wear and other clothing can be dated fairly accurately through the study of funerary monuments which, of course, usually show the date of the subject’s death. This “square” style of headgear was typical of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries after which it disappeared altogether. Taken with speculative dates of the towers, aisles and clerestories that they adorn we can be pretty sure that their carvers were active between about 1390-1420. That relatively short window, of course, strengthens the hypothesis that they all knew each other. In any event, though, their work is intermingled on so many of the churches that there is little room for doubt. This was not a “fashion”, not coincidence, nor even plagiarism. There was cohesion in the work of these men. Lets’ take a look at another recurring theme. I think it is supposed to be a flea but you are welcome to your own theory. The reason I opt for a flea is that they plagued people at this time but, of course, our masons would never have seen one close up because they hadn’t the optical wherewithal. Please don’t raise that hoary old nonsense about mediaeval bestiaries and their fabulous creatures. I’ve searched high and low for such a spiritual explanation and there is none! In any case, where the thump do we suppose a common mason would peruse a book of any kind - even if he could read? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fleas at Brant Broughton, Cottesmore, Whissendine, Langham, and Hungarton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are flea carvings also at Oakham and Buckminster. Still sceptical? Well at both Whissendine and Cottesmore the flea is right next to a mooner! How many carvings are we talking about? Well there are over 100 at Ryhall alone. I really can’t be bothered to count them at all the churches but I think between a thousand and fifteen hundred as a minimum. This was a serious and systematic business. We are not talking about the random carvings of a few individuals. So what bound them? We cannot know but the only plausible explanation, in my view, is that they were members of an itinerant guild of stonemasons. Masons could not operate outside of the guild and of course their work was essentially peripatetic. We are all familiar with the idea of secret signs in modern Freemasonry but this has its roots in the real freemasonry guilds of the mediaeval period. As with all guilds, there were masters, journeymen and apprentices. Masons in those days had secret signs to identify each other as well as skills of their craft that were revealed only to other masons. At churches, as well as at other building sites, they would have “lodges” (again, familiar in modern Freemasonry) used for planning and for carrying out more delicate tasks. It was surely within this closed world of the lodge that our masons thought up their laddish signature carvings. I call it the “Mooning Men Guild” and I believe its most likely base was in Oakham, the county town of Rutland, England’s smallest county. Why, you might wonder, would a church pay for this work? Well, the answer is that I don’t think they knowingly did. It is well known that the master mason would often be paid a fixed price for the whole job, even sometimes to include procuring the stone. If the master had labour being freed up towards the end of a project he could easily put men to decorative work. All the evidence is that it was mediaeval practice throughout the land to give the masons a free hand on decorative carving. We cannot know how many men were involved in the carving. We can be absolutely sure that they were ordinary masons first, decorative carvers as a sideline. Only the richest, grandest churches in the land could afford the highly-skilled and highly-paid “ymaginators” who carved such sculptures for a living. No parish churches could afford them and anyway the quality of the carvings is much too variable. Those at Ryhall in Rutland and Brant Broughton in Lincolnshire are arguably the finest. Those at Cottesmore in Rutland, for example, are very much cruder. Nor were these men master masons. There would probably have been only one of those on any given site and it seems unlikely that the roles of architect, planner, project manager, employer and purchasing officer would have left much time for indulging in a bit of decorative carving! We might not know how many there were but there are five whose work can be readily identified across two or more churches. I will come on to them shortly. So far we have been talking about frieze carvings. These are the vast bulk of the work in question. Our heroes did not, however, confine themselves exclusively to friezes. Many of these churches have similarly outlandish labels tops. You are wondering what a label stop is, right? Well many churches were surrounded by a raised stone moulding that directed rainwater around the outside of the window. This is a “drip mould” At each of the two ends of the drip mould would be a label stop - a raised bit that was sometimes decoratively carved. Many label stops were boring geometric designs. Others had human heads that many people like to think would commemorate local worthies - and I am sure that in some cases this is right. Label stops were also favourite places for heads of the reigning kings and queens. At some of the Mooning Men churches, however, we see more imaginative carvings, particularly at Ryhall. At Colsterworth there is even a mooning man label stop! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four label stops at Ryhall and (far right) a mooning label stop at Colsterworth |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

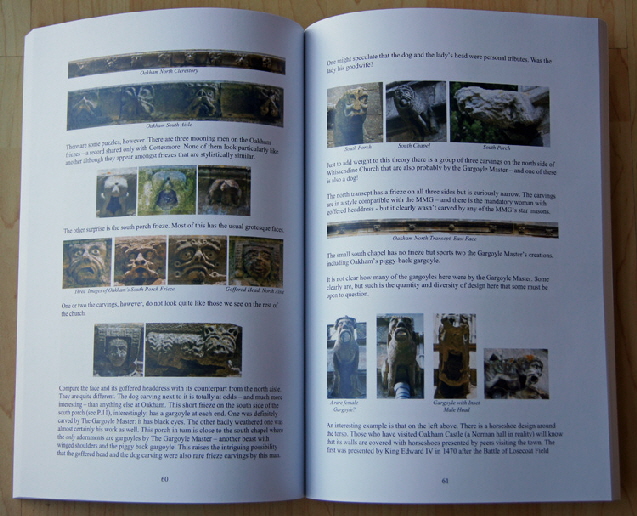

The Gargoyle Master My research was very much based upon the frieze carvings in the early days. I had always found gargoyles amusing, but the parade of endless grinning dragons with huge gobs is a bit repetitious. I woke up when I saw gargoyles at Oakham and Lowesby in Leicestershire that were patently by the same man. It is a distinctive design that has a woman riding on the back of the beast, and with another woman lodged between his legs - no there is no obvious sexual allusion. Once I opened my eyes I found more or less this same design at no fewer than six churches: Oakham, Lowesby, Owston, Empingham, Tilton-on-the-Hill and Wymondham (Leicestershire, not Norfolk). All but Empingham and Owston had friezes as well. The women “riding” the gargoyles had the familiar square headdresses seen on the friezes and some had still had black eyes such as found on the friezes at Ryhall and Oakham (see pictures above). It is blindingly obvious that they were all carved by the same man and that he was a mason of the Mooning Men Guild. I call them the “Piggy Back Gargoyles” There are other distinctive gargoyle designs and these are clearly identifiable by both their design and their location as being by this same man. In fact, his gargoyles are all over the Mooning Men Guild churches estate. I call this man “The Gargoyle Master”. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Piggy Back Gargoyles at Lowesby and Oakham. Gaping mouth (?) Gargoyles at Knossington and Wymondham |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gargoyle Master work at (first and second left) Tilton-on-the-Hill, (centre) Market Overton, (second right) Whissendine and (far right) Irnham |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Five Masons Besides the Gargoyle Master, there are four other identifiable styles attributable to individual masons. The names are, of course, purely my own and indicate the church or areas where each is best represented: “Ralf of Ryhall”: Ryhall, Oakham, Tilton-on-the-Hill, Langham, Lowesby, Cold Overton. Probably Thurlby. Possibly Careby. “Simon Cottesmore”: Cottesmore, Buckminster, Whissendine, Oakham, Hungarton. Probably Colsterworth. “Lawrence of Leicester” : Knossington, Wymondham, Lowesby, Tilton-on-the-Hill, Langham “John Oakham: Oakham, Whissendine. Also Muston and Bramt Broughton and possibly Bottesford all outside the normal Mooning Men Guild area. “The Gargoyle Master”: Oakham, Whissendine, Lowesby, Tilton-on-the-Hill, Market Overton, Wymondham, Knossington, Langham, Empingham, Owston, Irnham, Buckminster These men did not carve all of the friezes and gargoyles on these churches - remember these men were stonemasons, not decorative carvers so it is unsurprising that some carvings were one-off pieces of work. Thurlby, Careby and Colsterworth are the hardest churches to “place” and I have had to speculate. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Black Eyes Several churches have frieze carvings with eyes that have been made from lead or, just possibly in some cases, slate or other stone. After considerable heart-searching and poring over many pictures I am reasonably confident that only Ralf of Ryhall and The Gargoyle Master used this device. Let’s put this into context: in visits to several hundred churches I have never seen it elsewhere. You will occasionally see black eyes painted on interior carving but black paint could not possibly survive six hundred years on external carvings in the English climate. You will see several examples in the pictures above and you will see others where lead eyes have been lost. In quite a few cases you can see remains of the eyes and it is reasonably clear that the masons used more than one “technology” to attach them. There isn’t room to discuss that here but you will see more information in my book. The best collections of black eyes on friezes are at Ryhall, Lowesby and Oakham but the Gargoyle Master seemed to put then on all his gargoyles. It is this fact that convinces me that the key to the use of these eyes is in the availability of a plumber. We are not talking here of the modern definition of a plumber but of the original meaning as a man who worked in lead. This was a separate trade to that of stonemason and just as you would need to be a member of the masons guild to work in stone you would have had to have been a member of the plumbers guild to work in lead - not to mention having the material to hand and the tools to work it. When would the masons have a plumber in attendance? When roofs were being covered in lead and parapets added. When were roofs covered in lead? Often when aisles were increased in size and shallower pitched roofs were needed. When did most of the carvings occur? When aisles were added or rebuilt and/or clerestories were added. What often accompanied the leading of roofs? The addition of gargoyles to direct the rainwater from behind paraets and away from the walls. It all fits together quite neatly. The Gargoyle Master would almost by definition have a plumber in attendance. Ralf of Ryhall would sometimes add carvings when there was a plumber was available but when the plumber left so did his capacity to add the black eyes. This explains why almost every carving on the south side at Ryhall and on the clerestory had black lead eyes but the south side had none. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left to Right: Lowesby (Ralf of Ryhall); Cottesmore (Simon Cottesmore); Hungarton (Unidentified); Buckminster (Simon Cottesmore) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ralf of Ryhall at (left to right) : Cold Overton, Careby (speculative), Langham (speculative), Tilton-on-the-Hill |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Gallery of Sculpture |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John Oakham (three pictures left) at Oakham, Brant Broughton and Whissendine. Right: Ralf of Ryhall at Thurlby (speculative) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lawrence of Leicester at (left to right): Lowesby, Tilton-on-the-Hill, Langham and Wymondham |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Simon Cottesmore (three pictures left) at Whissendine and at (second right) Cottesmore . Ralf of Ryhall at Ryhall (right) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Simon Cottesmore at Cottesmore. Centre: Gargoyle Master at Oakham (speculative). Right: Ralf of Ryhall at Cold Overton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||