|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At some point small chapels were added at the west end of each side of the nave. When I visited I concluded that these positions would not have been unusual for Anglo-Saxon “porticuses” and I was quite gratified to see that Nicklaus Pevsner had made the same observation. Traces of what appears to be a pointed arch on inside of the south side of the nave rather spoils this beguiling notion. The Church Guide suggests a thirteenth century date for the south chapel and twelfth century for the north. The Church Guide also believes that they were demolished in the fifteenth century referring somewhat vaguely to the depopulating effects of the Black Death. I find that a bit unconvincing. Similarly the abolition of chantry chapels at the Reformation does not explain the demolition of what were surely very small structures. An Anglo-Saxon porticus would often have a very small entrance from the main part of the church or even not at all. It is plausible that the wider arches from the nave were subsequent alterations. It was long believed that the chancel was extended east at some point. The Church Guide debunks this notion noting that during replastering work the north and south walls appeared to be single phases of work. This explains the characteristically Anglo-Saxon quoining at the eastern corners that had previously been thought to have been reused. You will be visiting for the wall paintings though! Here again we have a touch of dating controversy. Clayton’s paintings, as well as those at Coombes and Hardham (but not those at West Chiltington) are attributed to the “Lewes School” of peripatetic artists and associated with the Cluniac Lewes Priory. We need to be clear here that there is no suggestion that the artists were themselves monks - although it is actually not provable that they were not so. The amount of detail in the paintings, however, indicates an intimate knowledge of the Bible and so clerical oversight is reasonably assumed. Like Hardham, Clayton Church was given to Lewes Priory in 1093 by its “owner”, William de Warenne. It was believed for a long time that the paintings were very early twelfth century. Some art historians have, however, seen Saxon or Byzantine influences and have suggested a date as early as 1080. Well that’s a bit of a curved ball because Lewes Priory was only founded in 1081 after Warenne had visited Cluny (in Burgundy). It seems to me that either this “school” was not associated with Lewes at all or those art experts are just spouting hot air. As far as I can tell, there is absolutely no proof - only a presumption - that Lewes was the common factor here but even to a bit of a sceptic like myself it seems pretty reasonable. On the whole, I think the art historians in question have just been contributing to global warming - but in truth nobody knows anything for sure about this period. The church is dominated by the great figure of Christ painted over the chancel arch. Angels support Him on either side. He is flanked by his Apostles. |

|

|

The great chancel arch painting. The central figure of Christ is almost identical to that at Coombes in the same county where you can also see the same pattern as you see here at the top of the wall. Another similarity is the appearance of the keyhole shape motif that you can see either side of the arch above the impost blocks. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. Note the elegant design of the late Anglo-Saxon chancel arch. Its aesthetics are very pleasing and the execution is of high quality. To the right of the chancel arch in the south wall you an see the remains of the pointed archway that would have led through to the long-disappeared thirteenth century south chapel. The east window in Early English triple lancet style dates only from the mid-nineteenth century but may well have replaced the real thing since the east wall was rebuilt in the thirteenth century. Right: The fascinating image of Christ. His off-the-shoulder gown seems to be of eastern origin and it is believed that the artists were influenced by Byzantine art. Certainly the keyhole-shaped arcading in the background would have had no British model to draw upon. The halo too is of unusually large proportions, rather more like eastern iconic art forms. .The positions of Christ’s hands are also unusual. They are raised to show his wounds. It is worth reiterating that it was not at all common to represent the crucifixion of Christ at this point in our history. The Christ of the Anglo-Saxon was a dominant figure. if He was shown on a cross at all he was conspicuously larger than surrounding figures with no signs of human suffering such was were to become common in renaissance art. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

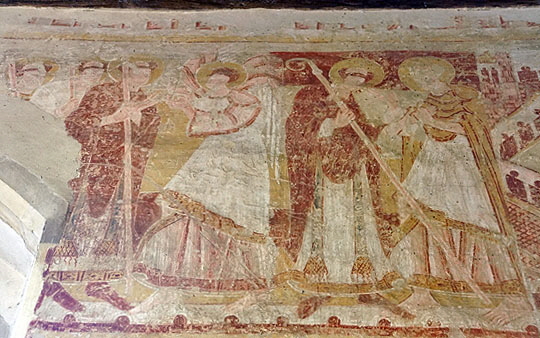

Left and Right: The Apostle figures that flank Christ on either side of the chancel arch. Note the angels that support the the elliptical shape frame within which Christ sits, The apostles are clad in white and are shown in informal groups. Note the absence of expensive green and blue pigments, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: On the right is an angel blowing the last trump. To his left is a six-sided enclosure representing the city of Jerusalem with St Peter within. Above the enclosure you can see a representation of a dome. This is very interesting. Domes were unknown in England. British architects had not developed the skills and techniques. In AD325 The Emperor Constantine had ordered the Church of the Holy Sepulchre over the supposed site of Christ’s crucifixion and it was completed in AD333. This had a dome. The church, however, was destroyed by Caliph Al-Hakim bin-Amr Allah in 1009. It was not rebuilt until 1149. So at the time of these wall paintings there was no church. There was, however, the Dome of the Rock that was also built in Jerusalem and was completed in AD693. Was the dome at Clayton, then, this Muslim shrine. Surely not? So why was there a dome here on this picture at all? How would the painters have known even of the former existence of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre that had been destroyed up to a hundred years previously? The knowledge must have come from a monastic library. When I saw this representation of Jerusalem in this hexagonal form it immediately reminded me of the remarkable mosaic map of the world on the floor of the Church of St George at Madaba in Jordan which I visited in 2006 and which shows a map of Jerusalem - the centre of the Christian world. It is known that the map could not have been made after AD570. It very clearly shows a golden dome which was surely the Church of the Holy Sepulchre which was still standing at that time. Did the monks at Lewes have an illustration of this map in their possession. Was it shown to the painters? Right: Jerusalem as shown on the Madaba mosaic world map. The dome is marked with an arrow. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

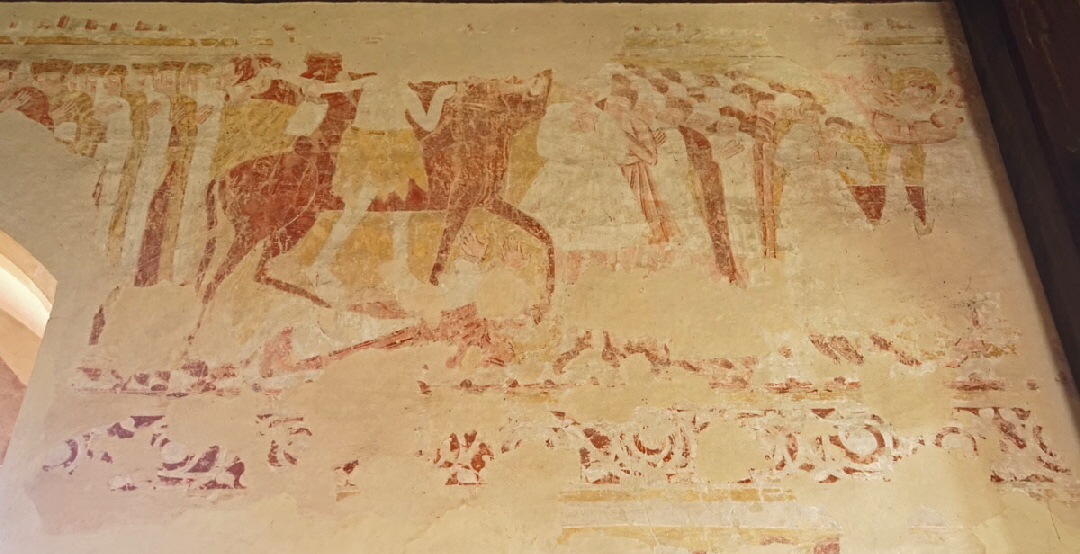

The horse is being ridden by a savage-looking figure, presumed to be the Devil. He is scantily-clad and his heels are sharp. It is difficult to see but he is dragging a man by his hair. Underneath the horse’s hooves a man is being trampled underfoot, his hands held up in horror. People look on from either side. To the left the figures are taller and their hands re. To the right they are more densely packed. All of the figures seem to have a hand held to their breasts and they are alternately in robes that are either coloured or white. What can this mean? All have the same style of round hat. Their faces are grim. Are these the damned? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

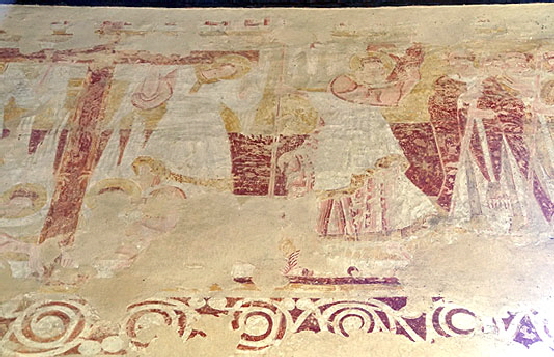

Left: The cross is being supported by four angels (two by the arms and two below). Right: St Michael stands to the right of the cross and is greeted by bishops with croziers. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A group of bishops and angels. To the right is the beginning of the representation of Jerusalem. Right: The Antichrist falls while an angel blows a horn triumphantly |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The reverse of the chancel arch looking towards the west. Right: The north door. There is nothing to positively date it but the irregular jamb stones and the simple curved arch certainly look to be Anglo-Saxon in keeping with the rest of the fabric. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is a very interesting brass memorial to Richard Idon, a rector who died in 1523. He is holding a chalice and a wafer and the whole gives a good idea of the appearance pf a typical English clergyman of the sixteenth century. Right: The church from the south west. It seems that the church turns its best face to the north rather than to then more usual south which has been chosen for the vestry which probably covers the original south door. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north east chancel showing the Anglo-Saxon style long and short quoining. The faux nineteenth century Early English lancet windows have been clumsily inserted into an original gothic window frame which itself replaced the original Anglo-Saxon one. The wall was rebuilt in the thirteenth century. Right: The church from the south east. the lancet windows are late thirteenth century but in between these on both sides are smaller and earlier blocked up windows, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||