|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

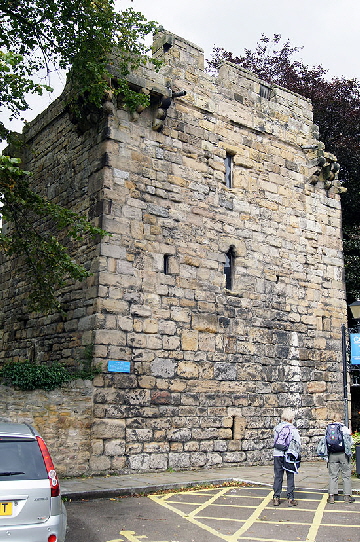

,by Robert Bruce in 1312, and in 1346 by David II of Scotland...” Phew! Corbridge was no place for the peaceful life, it seems. The first church here may have been built in around AD674 by St Wilfrid, one of the giants of first millennium Christianity in England. He had established nearby Hexham Abbey a couple of years earlier. It was certainly no later than the late eighth century because there is documentary evidence that a Bishop of Mayo was consecrated here in AD786. Much of the stone at Corbridge was filched from the abandoned Corstopitum. Much of this original foundation remains- the lowest part of the tower that would have at that time constituted a west porch, and the nave walls that are now pierced by later arcades. The tower was later raised but still before the Norman Conquest. The original west porch had buildings beyond it and these were probably monastic buildings. Indeed, most stone churches at that time would have been monastic. The original west doorway can still be discerned but has unfortunately been in-filled with an ugly three light window. This doorway has massive stone blocks each side laid successively upright, flat, upright, in what is known as “Escomb Style”. It is nearly ten feet high in keeping with the Anglo-Saxon love of height in their churches. Best of all , perhaps, is the tower arch within the church. It was apparently taken in its entirety from Roman Corstopitum. The south door is Norman from about 1128 but most of what we see today is Early English period extension of the original Anglo-Saxon plan, although there was considerable restoration work carried out in 1864-7. The exterior, as with so many churches in this area, is largely Early English in character with a predominance of tall lancet windows. These give the interior of the church a rather dark and foreboding atmosphere, somewhat in keeping perhaps with the town’s beleaguered history! The chancel arch of around 1220 is of extraordinarily tall proportions. We should not be surprised because the nave clerestory was cut into the original north and south walls of the church: it was not added later. Again, we see the Anglo-Saxon love of height. This arch leads to an Early English chancel which covers the Anglo-Saxon original. It is extraordinary for being both longer and wider than the nave. The arches of the arcade were, again, inserted into the original church walls in around 1250. Given the weight of the massive walls this was no small engineering achievement. Next to the church is a Pele Tower. That’s as in orange peel, by the way, not as in the Brazilian footballer! This is a “Vicar’s Pele” and the best surviving example of its kind. It is perhaps mid-fourteenth century and Corstopitum again donated the stone! Pele towers are common in the border region and offered protection from the marauding Scots. You see them standing alone or as part of old farm complexes. Vicar’s peles, however, are a peculiarly Northumbrian concept. Corbridge is well worth a visit for its town and not just for its church. It’s a quiet place but it seeps history from every pore and the church is very much part of that atmosphere. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: The west end. Despite the intrusion of the notice board, the original west door is still visible with its rather untidy mock triple lancet window insert. The window. The small round-headed window above is also Anglo-Saxon. Centre: The south porch. is mostly modern. from this picture you can see that the tower is quite small in ground plan compared with the church as a whole. This is not by design but because its base was just the western porch of the original much smaller church. Right: The Norman south door is the only real evidence of this period because the church is predominantly an Early English expansion around an Anglo-Saxon core. It is simply decorated with two courses of chevron mouldings. The Church Guide believes that it was added by Henry I’s chaplain who was vicar here in the 1120s. The pink and black staining of the stonework is not inherent in the stone but was caused by fire and smoke from Scottish raids. There is an attractive glazed inner door in which your truly has been reflected. It only looks like I am standing in a (non-existent) open northern doorway! |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: The blocked west doorway. Note the three massive stone blocks laid either side. You can see that there are actually outlines of two arches here. Centre: The Roman tower arch probably dates from around AD200, the reign of the Syrian, Septimius Severus. It is 14.5 metres high! Right: The view west. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The soaring Early English chancel arch is as impressive as the Roman tower arch that it faces. Note also the almost equally lofty arcades to north and south. They are testament to the extraordinary proportions of the original church. These walls were the original outside walls of the Anglo-Saxon nave. There would have been no aisles. The chancel would have been considerably narrower - about twelve feet is the best estimate - and shallower. The west end would have had a porch, not a tower. It would, in short, have epitomised the Angl-Saxon love of height in their monastic churches. Centre: The tower from the south. On its east side just below the clock you can see another round-headed Anglo-Saxon window. This would have opened into the uppermost roof pace - a loft - and shows that the roof peak would have been even higher than it is now. The clerestory windows, of course, are a modern addition. Right: The lady chapel to the north of the chancel. It too is an Early English addition of between 1220 and 1280 as evidenced by yet another lancet window at its east end. It would be quite unusual to see this further south where the massive church expansion of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries saw aisles and chapels widened and roofs made more shallow. |

|

|

||

|

Left: The Early English chancel with its triple lancet windows. Although this would have been the original window configuration, both stonework and glass were renewed in the nineteenth century. Note the lady chapel arcade to the left and the priest’s door to the right. Right: The church from the south. Note the great height of the chancel (see also the title photograph) with its extraordinarily steeply-pitched roof. It is almost as if the medieaval masons were trying to compete with their Anglo-Saxon forbears. Actually, it is worth mentioning in passing, that really the masons in this part of the world would have surely been Angles and not Saxons. It is easy when talking of the Anglo-Saxon period to forget that the insurgent Germanic tribes settled in quite different areas and Northumbria is considerably to the north of the original Saxon sphere of influence. |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left and Above Right: Ancient windows. Below Right: The south aisles has this single corbel of tragedy and comedy. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|